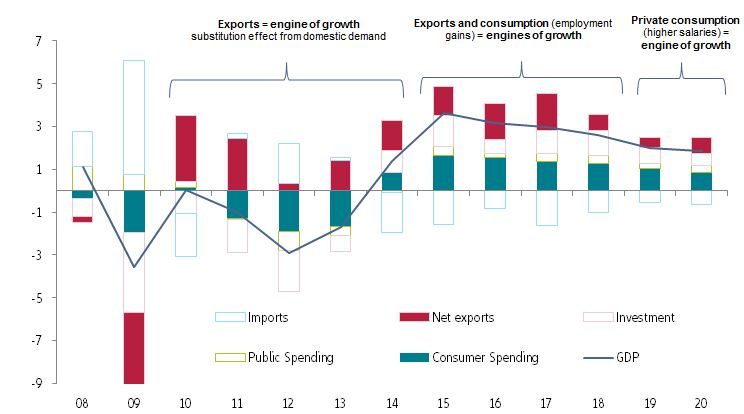

- Between 2014 and 2018, Spain experienced a second economic miracle: GDP grew by +2.8% on average p.a., exports grew by +4.2% on average p.a. and 2.6mn Spaniards were brought back to work. The 2010 and 2012 competitiveness reforms help explain this outperformance but the share of workers’ wages in national wealth dropped from 54.7% in 2010 to 51.8% in 2017.

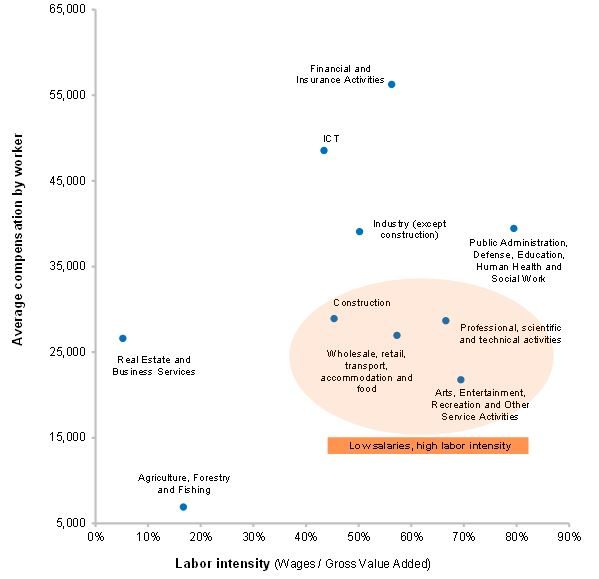

- In January 2019, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez increased the minimum wage (Salario Mínimo Interprofesional or SMI) by a whopping +22.3% to rebalance the economy, and partially offset growing social discontent. We estimate that this measure could have a net positive impact of +0.1pp on GDP growth in 2019, but a negative impact of -0.1pp in 2020 as competitiveness drops. Companies’ margins are expected to be indented by -1pp to 42% of value-added, and the measure could also cause around 100 additional insolvencies in 2019, especially in the construction and service sectors, but also among some exporters.

- The elections on April 28 will plausibly yield a fragmented political landscape, making structural reforms harder to pass. Our forecasts for Spain point to a deceleration to +2% growth in 2019, and +1.8% in 2020 – from +2.6% in 2018. In 2019, the SMI boost barely compensates for: (i) the slowdown in foreign demand, which could reduce export growth from +2.3% in 2018 to +1.0% in 2019, subtracting -0.4pp from Spain’s GDP growth, and (ii) the deceleration of domestic demand (consumption, investment and public expenditures) on the back of slowing employment gains. In 2020, as growth in major trade partners rebounds, Spanish exports would follow (+1.5%), this time with a drag from higher wage bills, marking the end of the Spanish miracle.

The Spanish miracle: An economic remontada

Between 2014 and 2018, Spain experienced a second economic miracle: GDP grew by +2.8% on average p.a., exports grew by +4.2% on average p.a. and 2.6mn Spaniards were brought back to work. One of the first and key drivers of the Spanish miracle was buoyant export growth, which lead to a rise in the share of exports in the overall economy (from 26% of GDP in 2008 to 33% in 2018). In the post-crisis years, Spain also increased its share of world goods exports at a faster pace than other EU countries, such as Germany and Italy. The IMF points out that as more firms began to internationalize, the number of regular exporters in Spain rose by nearly one-third between 2007 and 2017. Recent literature shows that Spain’s real export growth can mostly be explained by two drivers:

Cost competitiveness.

Spain’s growth in exports is not attributable to higher export quality: The MIT Economic complexity index shows that Spain’s export quality has not recovered from the crisis. In 2017, the knowledge-intensity of exports (a proxy for export quality) was still 23% lower than in 2008.

This export recovery is not because of productivity gains either: Looking at annual productivity growth in Spain, we see it did not outpace that of the Eurozone after the crisis except in 2012 and 2013 (see Figure 1). At the same time, the growth in the Unit Labor Cost or ULC (which is the ratio of total labor compensation per hour worked to output per hour worked, i.e. labor productivity) was systematically lower than that of the Eurozone starting from 2009.

This shows that Spain’s competitiveness gains were mainly due to adjustments in total labor compensation rather than productivity gains. In 2010 and 2012, Spain implemented labor market reforms to facilitate the adjustment of wages downwards in a high-unemployment context. According to estimates from the OECD (2014), these labor market reforms induced a drop in the growth of Spain’s business sector ULC of between -1.2pp and -1.9pp from Q4 2011 to Q2 2013. Overall, between 2008 and 2017, the nominal unit labor cost index decreased by -6%. This competitive devaluation of labor costs helped facilitate the adjustments of company activity to economic shocks and boosted export performances.

Foreign demand.

As a consequence of geographic diversification, foreign demand strongly contributed to the acceleration of real export growth. The EU’s share in Spanish goods exports declined from 73.1% in 2000 to 70.9% in 2007, and even further to 66.3% in 2017. By targeting fast-growing emerging and developing markets Spanish companies boosted their exports.

Following the recovery of exports, private consumption started to grow again in 2014, lifted by a favorable investment cycle and employment gains. Data from the national statistics institute show that between 2007 and 2013, the domestic economy lost around 3.6 million jobs, then recovered, creating 2.6mn jobs between 2013 and 2018. The opportunities created by the export miracle allowed companies to restart their investment cycles, re-igniting their hiring cycles to support their growing activity, while benefiting from a high bargaining power: unemployment peaked at around 27% in 2013, while labor market reforms decentralized wage negotiations.

In addition, looking at the growth of compensation by sector between 2008 and 2013, we find that the construction sector (-60%), the manufacturing sector (-23%), the real estate sector (-23%) and the retail, accommodation, transport and food sector (-9.3%) have seen their wages adjust the most. Then, looking at the employment gains between 2013 and 2018, many of those same sectors hired relatively more than the rest: 260,000 new employees in construction, 800 000 in retail, accommodation transport and food, 200 000 in industry. Beyond the cyclical recovery, it is likely that the wage adjustment we described also contributed to the employment gains.

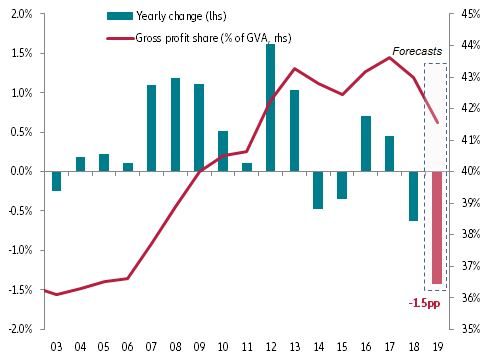

Companies reaped the rewards of the Spanish economic miracle

Insolvencies dropped for four years in a row before stabilizing in 2018, while turnovers kept pace with nominal GDP growth (see Figure 3). Besides, companies’ profit share of private sector GVA reached a record high of 43.6% in early 2018 - higher than the Eurozone average high of 41% - and self-financing rates (the ratio of gross capital formation to gross savings) were also maintained at high levels (see Figure 4). This is not only attributable to the global cyclical recovery and accommodative monetary policy in the Eurozone but also to the business-friendly reforms adopted in Spain (labor market reforms and corporate tax rate cuts by 10pps, from 35% to 25%, between 2006 and 2016 ). This coincided with a drop in the share of labor and tax costs over private sector GVA by respectively -7pps and -3pps (see Figure 5).

Figure 3 Growth in insolvencies, turnovers and GDP