Executive Summary

- Record-high inflation in advanced economies is turning up the heat on central banks. With average wages set to rise significantly in 2022, they face a difficult choice: overlooking the overshoot to protect the post-Covid recovery or tightening quickly to stave off a potential wage-price spiral that would add fuel to the fire.

- While we expect inflation to recede by 2022 as pandemic-related disruptions ease, if we were to experience sustained rising prices, the UK and France could be most at risk of a wage-price loop materializing in end 2022 and 2023, respectively. We find that, in this risk scenario, the wage-price loop could push inflation up by +3pp in the UK and +1pp in France by end-2023..

Record-high inflation in advanced economies is turning up the heat on central banks. With average wages set to rise significantly in 2022, they face a difficult choice: overlooking the overshoot to protect the post-Covid recovery or tightening quickly to stave off a potential wage-price spiral that would add fuel to the fire. After having remained near zero over a decade, record-high inflation in advanced economies puts central banks under strong pressure to act. Due to buoyant demand and persistent supply bottlenecks, end-2021 (year-on-year) inflation reached a record high of 7% in the US but also 4.9% in the Eurozone, 5.6% in Germany, 5.1% in the UK and 3.4% in France. After being concerned about “too low” inflation over the past decade, central bankers are now facing a new dilemma. Should they tighten monetary policy rapidly and strongly to revert an inflationary spiral with a looming wage-price loop? Or should they overlook the inflation overshoot for now to avoid tightening too early and too much, which could stall the recovery as the Covid-19 crisis turns endemic .

The interaction of goods and labor markets will play a key role in maintaining or amplifying the inflationary momentum. A wage-price loop is composed of two phases: First, the initial price shock being transmitted to wages, followed by a potential feedback effect from wages to inflation as firms adjust their prices to compensate for rising wages and costs.

Several factors set the stage for a wage acceleration in 2022: rising price pressures, the indexation of wage increases to inflation but also difficulties in recruitment (negative supply shocks or insufficient supply capacity to meet rising demand, eg. due to skill mismatches, limited geographic mobility and the structural transformation of the global economy after the crisis). Higher salaries to attract workers in tight sectors and composition effects (as low-skilled/less-productive workers who have lower salaries tend to lose their jobs first) will also come into play. In addition, the expected continued decline of unemployment rates (i.e. closing output gaps) will build upward wage pressures. In this context, stronger wage increases are more likely this time around compared to the period after the 2008 global financial crisis..

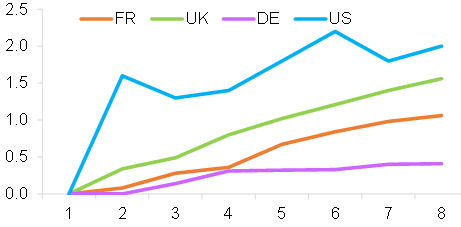

While we expect inflationary pressures to recede in the second half of 2022, stronger average wage growth is likely in the US (+4.7%) and the UK (+3.5%), while France and Germany should both see wage growth of +2.5% on average (Figure 1). In the US and UK, this reflects the greater flexibility of labor markets but also a changing labor force composition (declining share of low-wages during the sanitary crisis), the drop in the participation rate (especially in the US) and labor shortages (more pronounced in the UK after Brexit).

In France, wage growth will follow inflation in 2022 while in Germany it will be more moderate.The historical decomposition of our VAR analysis (see Appendix) shows that in France the moderation of nominal wages largely contributed to decceleration of inflation as of 2011, but the situation is likely to reverse with a significant cath up in wage acceleration, looking ahead. The quasi-generalized wage increase agreement in the French banking sector in 2022 –for the first time in 10 years – is one exemple among many others.In Germany, where wages tend to be negotiated in line with economic and productivity developments, there is less room for such a catch-up effect. After a decade of wage moderation under Harz IV reforms, nominal wages showed already a persistent and positive contribution to inflation dynamics in Germany as of 2011.

Figure 1 - Our baseline inflation and average wage increase projections (% increase y/y)

If current pressures do not reverse in 2022, the amplification mechanisms could shift advanced economies towards a high-inflationary regime. In this context, we find that the UK and France would be most at risk of a wage-price loop materializing already in end-2022 and 2023, respectively. Generally speaking, , if a price shock is temporary or followed by a reversal, the pass-through to inflation would be limited. We point out in our baseline scenario that a reversal in energy prices and/or a normalization of the tensions in supply chains in the coming quarters may be sufficient to release current inflationary pressures before they diffuse more permanently in labor markets. On the other hand, the prolonged acceleration of energy prices and supply bottlenecks, as well as “green regulation” (i.e. a carbon tax), constitute a significant upward risk to our baseline inflation and wage forecasts.

To investigate how quickly a price shock (e.g. triggered by rising imported goods prices) spreads to overall prices and labor markets, we conduct a structural vector autoregressive model (VAR) analysis (see Appendix for methodology). While wages in the US, UK, Germany and France all react to exeogenous price shocks, there are big differences in magnitude and diffusion dynamics (see Figure 2). In continental Europe (France and Germany), the reaction of wages to price increases occurs with an around two-quarter delay and the resulting wage increase barely matches the indexation of wage increases to inflation. For instance, a 1% price shock would increase average wages by 1% in France after a year and a half. This delayed reaction of wages to price increases in France and Germany seems to reflect the wage-adjustment mechanisms that take place mainly through a lengthy wage-negotiation process, which typically occurs once a year. In Germany, the weak reaction of wages to price increases is certainly the outcome of wage moderation in the past via collective bargaining agreements to preserve competitiveness .

On the other hand, in the US and the UK, wages seem to react rapidly and strongly to price changes, certainly reflecting greater labor market flexibility. The UK appears to be in an intermediate position, with stronger and quicker wage increases compared to France and Germany. A 1% price shock in the UK already leads to a full indexation of wages after a year. In the US, where the labor market is most flexible, wages appear to adjust immediately and strongly to price shocks. After just one quarter, US wages appear to increase more than the initial price shock.

Figure 2 - Diffusion of 1% increase in prices to wage growth (impulse responses), X axis: Number of quarters, Y axis= % increase in wages

Firms facing cost increases – through both higher input prices and higher wage costs – eventually adjust their selling prices, which in turn can generate greater and more persistant inflation compared to the initial price shock. How long firms can absorb cost increases depends on the nature of the price shock (temporary or persistent), the degree of competition and their financial health (i.e. cash buffers). Our model shows that in Germany and the UK, wage increases are simultaneously passed on to prices, whereas French firms absorb wage increases into their margins for almost four quarters. Importantly, in the US, prices do not seem to be affected by wage developments (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Diffusion of 1% increase in wage growth to prices (impulse responses), X axis: Number of quarters, Y axis= % increase in prices

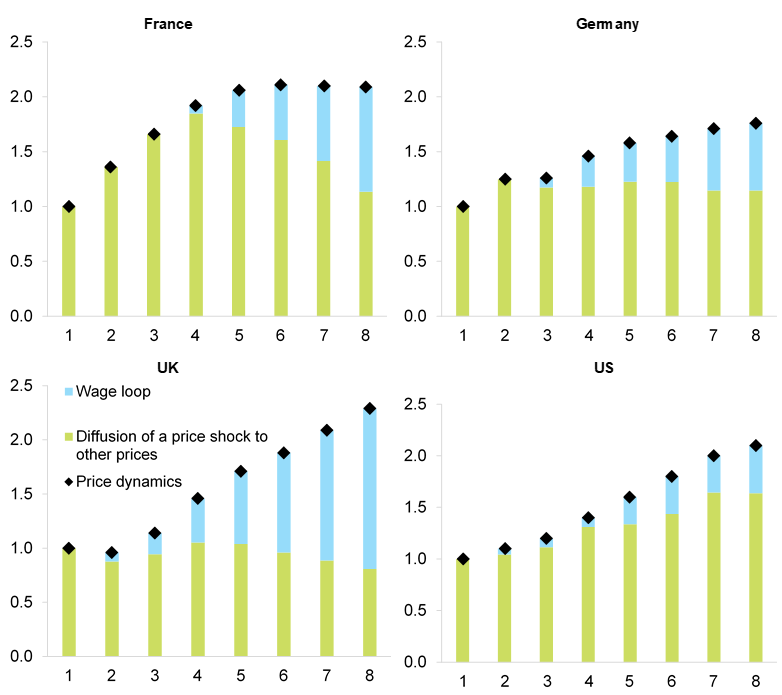

Based on the VAR analysis above, we illustrate in Figure 4 the combined diffusion of a price shock to downstream prices and through the wage-price loop (see Appendix for methodology). In all countries, the brunt of price dynamics largely comes from the diffusion of the initial shocks to downstream prices (green bars in Figure 4).To illustrate, a sizeable price shock on construction material would be passed on to downstream prices over time, such as rents. Overall, after eight quarters, the magnitude of the initial price shock almost doubles, if inflationary factors do not revert in the meantime. We find a strong and immediate price diffusion in France, potentially reflecting weaker pressures from competition and/or lower profit margins. In the US, the diffusion of a price shock would be weak in the first year but increase afterwards. Finally, in the UK and Germany, companies appear to absorb the (input) price shock into their margins until the strong reaction of wages to a price shock increases production costs significantly.

Figure 4 – Decomposition of the diffusion of a 1% price shock, X axis: Number of quarters

In an alternative scenario of continued high inflation throughout 2022, the contribution of the wage-price loop (see blue bars in Figure 4) to overall price increases is the strongest in the UK as price shocks are rapidly and strongly amplified by labor markets. For instance, the +2pp upward surprise to inflation in H2 2021 is set to amplify inflation through the wage-price loop by +0.8pp (cumulative) by end-2022 and by +3pp by end-2023. When we add the second round (price-diffusion) effects and the wage-price loop together, the +2pp initial inflationary shock in H2 2021 would raise inflation (compared to our baseline) by +1pp by end-2022 and by +2.6pp by end-2023, if inflationary factors (e.g. imported input and energy prices) do not normalize in the meantime.

On the other hand, in France, we also find a strong wage-price loop but its impact is alleviated by the delayed reactivity of this mechanism during four quarters. Accordingly, the +1pp inflationary surprise in H2 2021 would feed back to inflation via the wage-price loop by +0.3pp by end-2022 and by +1pp by end-2023, if there is no reversal of inflationnary conditions. In Germany, the wage-price loop also appears with some delay (three quarters) and is of smaller magnitude compared to France. A +1pp. upward shock to inflation in H2 2021 would create a wage-price loop by +0.4pp by end-2021 and by +0.7pp by end-2022. Another key finding about Germany is the weak diffusion of the inflationary shock to other downstream prices, perhaps due to greater market competition. For instance, a +1pp shock to prices in H2 2021 would only be amplified by +0.2pp by end-2022, versus by +0.8pp in France.

Interestingly, the risk of a wage-price loop is limited in the US because of weak transmission from wage increases to prices. Although in the US wages react strongly and immediately to upward prices, the weak transmission from wage increases to prices alleviates the overall wage-price loop. When we take the combined effect, the +2pp inflationary surprise in end-2021 is set to generate only a +0.2pp of wage-price loop by end-2022 and a +0.5pp by end-2023. This moderate reaction may be explained by the ability of US firms to substitute capital for labor or to maintain access to a cheap labor force in the most labor-intensive industries. However, the overall effect – coming mainly to the diffusion of the initial nominal shock – is comparable to the other countries. A +2pp price shock by end-2022 would be doubled by end-2023, as it is also the case in France and the UK.

In the context of a “cost” inflation time bomb, central banks need to master the timing of their policy actions to prevent the amplification spiral. Even though monetary tightening would have limited impact in tackling supply pressures, it should help alleviate price pressures by taming demand exuberance. In this sense, the Bank of England already started to raise its policy interest rates end-2021 (+15bp) and will increase rates at least twice in 2022 (cumulative +50bp) to prevent the looming wage-price loop. To avert an inflationary spiral, the Fed is also already dialing back its accommodative stance by speeding up the pace of tapering: three rate hikes at least are expected in 2022. In line with our empirical findings (i.e. the delayed response of wages to price shocks in continental Europe), the ECB appears to be in a position to tolerate some overshoot in inflation and wait longer before acting.