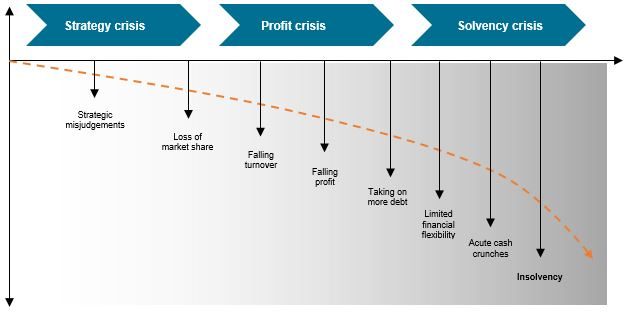

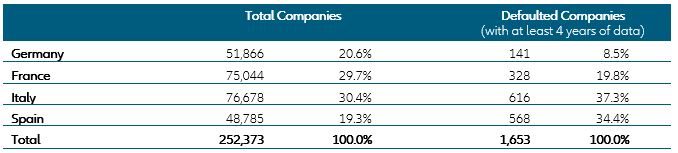

- Most insolvencies of European SMEs & MidCaps do not come as a surprise. In fact, they are typically the consequence of ongoing corporate distress over several years. Looking at 1,653 companies in Germany, France, Italy and Spain, we identify three phases, each different in type and length: a strategy crisis, a profitability crisis and then a solvency crisis. Once the profitability crisis sets in, corporate distress can be detected and observed by a systematic analysis of a company’s financial situation.

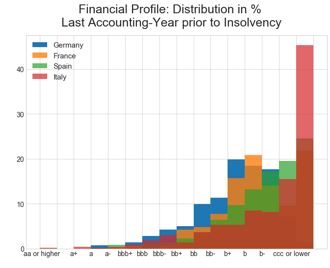

- In all four countries, the mean financial profile of all the insolvent companies we analysed was relatively low four accounting years prior to insolvency. German companies attained a mean financial profile of less than BB-, while the French, Italian and Spanish firms scored around B+. By the last accounting year before the insolvency, the scores decreased considerably down to below B+ in Germany, B- in France and around CCC in Italy and Spain. In comparison, the mean financial profile of all SMEs & MidCaps in the four countries is about BB.

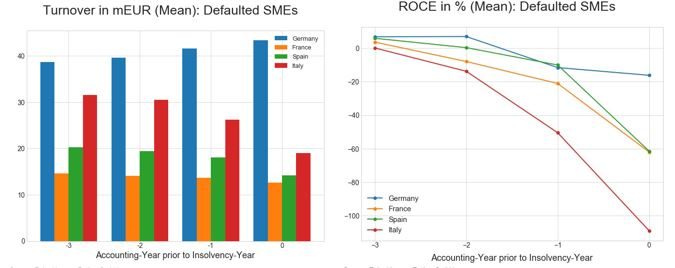

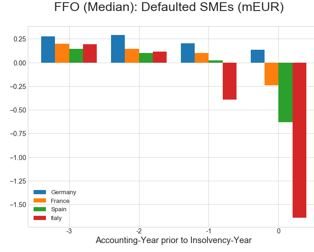

- Which leading indicators could allow us to detect corporate distress early? The literature often identifies a decline in turnover as an initial symptom, but our analysis shows that turnover development is not a robust indicator of corporate distress or increased credit risk in Germany. While it looks more effective in France, Spain and Italy, it’s not fully reliable. Instead, we find three indicators which can point to corporate distress three to four years before an insolvency.

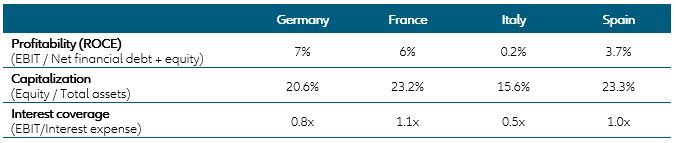

- The first and most important indicator is profitability. Four years prior to an insolvency, the average Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) is relatively weak: around 7% for German SMEs, 6% for French SMEs and below 4% for Spanish SMEs. In Italy, ROCE is almost close to 0%. In comparison, the average ROCE of all SMEs & MidCaps in the four countries is between 10% and 14%. As corporate distress unfolds, companies' profitability decreases significantly, falling deep into negative territory one year before an insolvency.

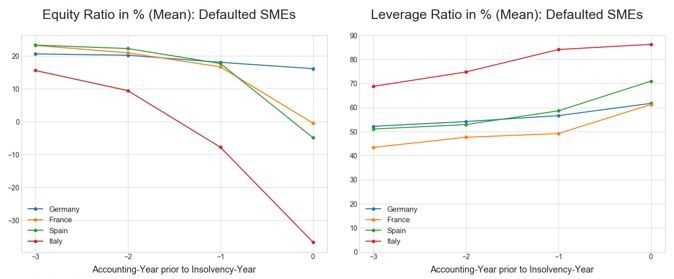

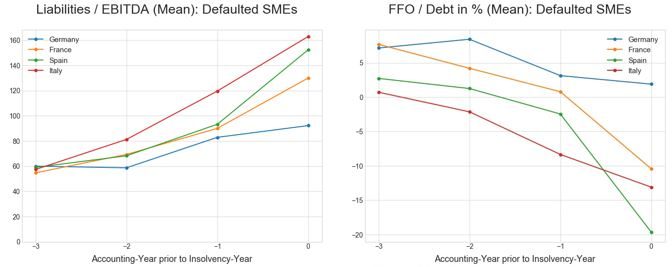

- The second indicator is capitalization, which tends to decline along with the decline in earnings, albeit at a slower pace. Four years before their insolvency, companies have average equity ratios of 20.6% (Germany), 23.2% (France), 15.6% (Italy) and 23.3% (Spain). In comparison, the average equity ratio of all SMEs & MidCaps is about 30%. Capitalization deteriorates significantly in the last year prior to insolvency, resulting in over-indebtedness in all countries except Germany. As earnings and capitalization deteriorate, the resulting negative impacts on credit risk clearly affect the deleveraging potential[4] as well.

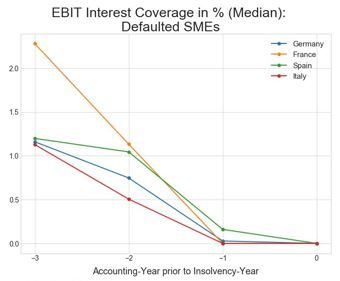

- The third indicator for corporate distress is the interest coverage. As early as three accounting years before an insolvency, companies’ average EBIT-based interest coverage is very weak: between 0.5x in Italy, 0.8x in Germany, 1.0x in Spain and 1.1x in France. Compared to this, the average interest coverage of all SMEs & MidCaps is about 3x. In other words, at this early stage, operating profits are already or close to being unable to cover interest expenses.

In most European countries, the number of corporate insolvencies has risen slightly since 2018 after several years of steadily declining or staying low. It is still not clear whether this shift represents a full-fledged trend reversal, but to us that seems to be the case, given the weakening economy and growing pressure for change due to ongoing structural shifts. While insolvencies ought to increase gradually and not spike all at once, absent an exogenous shock, companies, lenders and investors should look more closely at the credit risk component of their decisions going forward. In this paper, we identify how the insolvency risks of SME & MidCaps can be detected at an early stage, starting with the typical pattern of corporate crises. The findings are based on a statistical analysis of insolvent European SMEs & MidCaps in Germany, France, Italy and Spain.

SMEs & MidCaps go through three phases of corporate distress prior to insolvency

Most insolvencies of European SMEs & MidCaps do not come as a surprise. In fact, they are typically the consequence of ongoing corporate distress over several years, which can be detected by a systematic analysis of a company’s financial situation. We identify three phases companies go through, each different in type and length, before facing an acute insolvency risk (see Figure 1): a strategy crisis, a profitability crisis and then a solvency crisis.

In the first phase, companies still have a relatively wide range of strategic options available to cope. However, if they fail to recognize the situation, the corporate distress will intensify and their available options will shrink substantially as they enter and move through the second phase. In the final phase, their options tend to be so limited that it becomes extremely difficult to avoid a potential default.