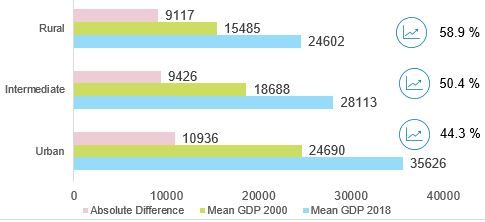

- In Europe the popular narrative of people in the countryside being left behind, while urban elites benefit from globalization and technological change, is used to explain everything from the Brexit vote to France’s Yellow Vest movement. However, we find that Europe’s rural areas aren’t really losing the economic development race: over the last two decades, they grew faster than urban ones by a whopping 14.6pp. The poorest areas across 24 European countries have moved closer to the average in terms of GDP per capita and the number of areas in the middle of the income distribution has also increased.

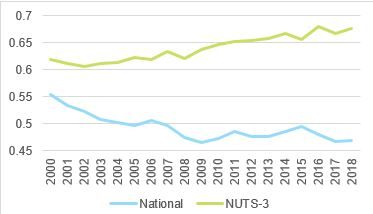

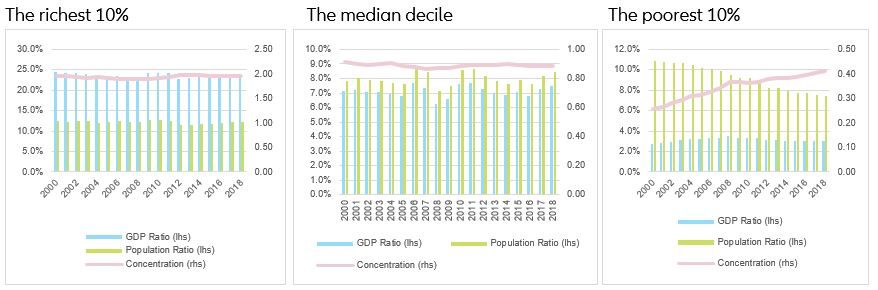

- But does convergence lead to more equality, i.e. are poor areas growing fast enough to close the absolute gap with richer ones? Here the picture is mixed: At first glance, disparities are rising due to the outstanding performance of a handful of “super-champion” areas in Europe, namely urban ones. But GINI coefficients and income concentration measures do paint a more nuanced picture, indicating improvements for the poorest regions over time. The GINI-coefficient for all European areas dropped from 0.26 in 2000 to 0.25 in 2018, meaning that there is (slightly) less inequality between the areas.

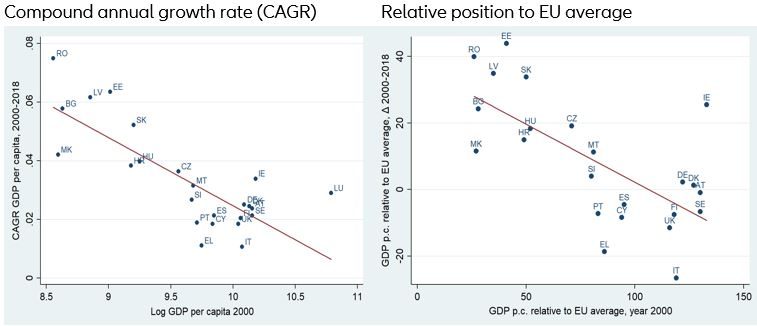

- However, urban areas are the driving forces behind national convergence in Europe. We find that countries with lower initial GDP per capita levels – mainly Eastern and central European ones – show significantly higher growth rates, allowing them to improve their relative position, measured as GDP per capita as a percentage of the EU average. All in all, new EU members (Romania, Estonia) experience real income convergence, while old members (Greece, Italy) are mostly losing ground. However, the cost of catching up for Central and Eastern European countries is increasing divergence between urban areas and others.

Urban-rural convergence: Poor, rural areas are catching up

The popular narrative goes that Europe is facing an ever-widening urban-rural divide: People in the countryside are being left behind while urban elites reap all the benefits of globalization and technological change. But does this narrative hold against close scrutiny? A lot of work has been done on assessing general diverging/converging economic and societal trends in the European Union (e.g. recent publications by Alcidi (2019); Butkus et al (2018)). But the analyses mainly concentrate on comparisons of developments between old and new member states, or on the divide between Central, Eastern and Southern European countries. Instead, our research focuses on a rigorous urban-rural typology to approach the following questions: Do we observe areas in the EU converging towards their average over time? And are rural areas really losing the race for economic development?

Research by Barro & Sala-i-Martin (1992) was the first to popularize the concept of “beta convergence”, which represents a negative partial correlation between the initial GDP level and the growth in income over time. This is equivalent to saying that poorer countries grow faster than rich ones and thus catch up over time in economic terms. Digging a little deeper, we look at the catch up process across 24 countries in Europe separately by urban, intermediate and rural area averages. All in all, our data set consists of 1,078 areas for which GDP per capita in PPS (Purchasing Power Standard) is available for the years 2000 to 2018.

Figure 1 contrasts the initial level of GDP in 2000 with the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR).

We find a significant downward sloping regression line, which confirms that over the last 20 years rural-urban convergence has taken place. There is, however, a significant difference between the types of areas. While the regression line for rural and intermediate areas is a prefect downward sloping line, the regression line for urban areas exhibits a significantly smaller slope. This is further supported by the smaller R2 of the regression: While for rural areas roughly 48% of the variation in annual growth rates can be explained by initial GDP levels, the corresponding figure is only 4% for urban areas.