- The prevailing debate about zero and negative interest rates is increasingly focused on long-term negative effects: inequality, poverty in old age, zombie companies and financial market bubbles.

- In contrast, we calculate the direct effects of the European Union’s (EU) interest rate developments on each economic actor by using the net interest income (interest payments received minus interest payments made); particularly, we cumulate the annual changes from 2008 – the year in which the European Central Bank's (ECB) current easing cycle began – to 2018.

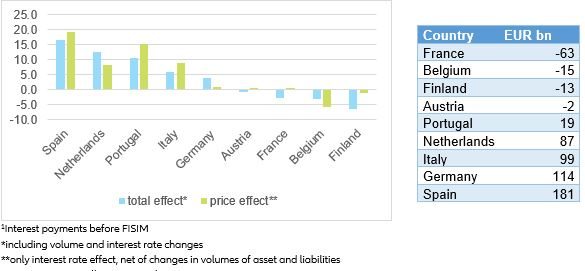

- ·The results are quite surprising: the overall benefit of low interest rates is neither equally distributed nor follows the North-South divide. Among the major beneficiaries are not only Spain (+16.5% of GDP or EUR 181bn) and Portugal (+10.4% or EUR 19bn) – as expected – but also the Netherlands (+12.7% or EUR 87bn) and, to a lesser extent, Italy (+5.9% or EUR 99bn) and Germany (+3.9% or EUR 114bn). On the other hand, Finland (-6.4% or EUR -13bn), Belgium (-3.0% or EUR -15bn) and France (-2.9% or EUR -63bn) are unexpectedly on the losing side.

- Furthermore, the development of net interest income varies also greatly from sector to sector. Three observations are particularly striking:

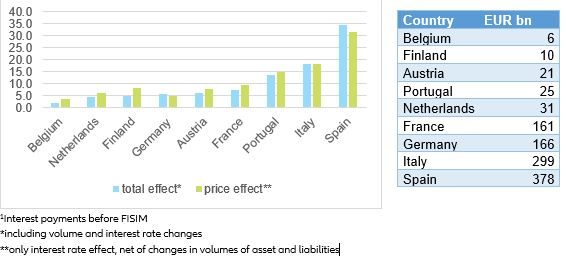

- Firstly, only non-financial companies have consistently benefited from the low interest rate environment. Highly indebted companies in Southern Europe saw particularly large positive effects, ranging from 13.5% of GDP in Portugal (EUR 25bn) and 18% in Italy (EUR 299bn) to 34.5% in Spain (EUR 378bn).

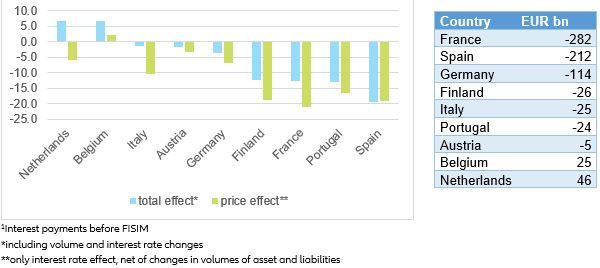

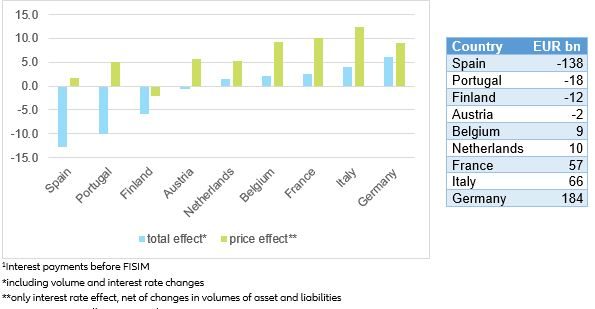

- Secondly, not all governments were able to benefit from the fall in interest rates. Rising debt levels in some countries have eaten up the savings from lower interest rates. Germany has improved its (negative) net interest income the most (+6% of GDP or EUR 184bn), as the decline in interest rates has been accompanied by debt restraint. On the other end of the spectrum sits Spain: Its public net interest income deteriorated by 12.7% (EUR -138bn) as public debt increased threefold.

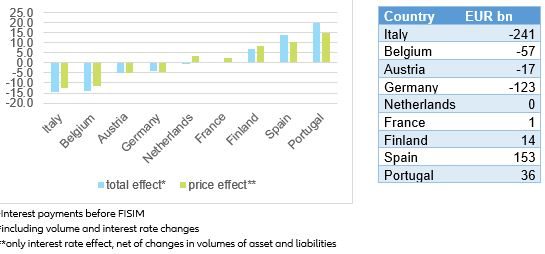

- Thirdly, the situation of private households is very heterogeneous, driven by behavioral changes, the proportion of savings and debt and the pass-through of interest rate cuts on the credit side. All these factors led to German households suffering from low interest rates – to the tune of 4.2% of GDP (EUR -123bn) – while Spanish (+14.1% or EUR 153bn) and Portuguese households (+20% or EUR 36bn) benefited the most.

- All results can be replicated with the “Allianz Net Interest Income Calculator”, which measures the net interest income of the four main actors (government, households, non-financial companies and financial corporations) in the individual euro countries since 2002.

What do we measure when we measure net interest income

Net interest income is the difference between interest income (e.g. household interest income from bank deposits and bonds) and interest expenses (e.g. household interest payments on loans).

For the “Allianz Net Interest Income Calculator”, we use interest payments before Financial Intermediation Services, Indirectly Measured (FISIM, see box below) and take changing volumes into account. This is because there have been changes in volumes in recent years, in some cases drastic, also as a conscious reaction to the low interest rate environment.

We measure the net interest income of the government, households, non-financial companies and financial corporations in the individual Eurozone countries from 2002 to 2018. More specifically, to capture the development since the start of the current monetary easing cycle, we cumulate the annual changes against the year 2008 and express the sum as percentage of GDP. This way, we are able to gauge the impact of the low-yield environment in just one key number.

Box: What is FISIM?

The national accounts refer to two forms of interest income and expense: before and after "FISIM", which stands for "Financial Intermediation Services, Indirectly Measured". This is calculated by adding/deducting the indirect fees charged by banks as part of their lending and deposit business, calculated using models, to/from the interest payments actually made.

In other words, the national accounts assume that interest payments consist of two components: the "pure" interest and the price for the banking service (e.g. loan processing, deposit management, etc.). This is why, for example, the interest income of private households is much higher after FISIM – after all, this income also settles any service fees relating to account management which the banks, however, conveniently withhold right away (which is why they are referred to as indirect fees). Interest expenses, on the other hand, are much lower, because part of the interest payments “actually” refer to the service fees for loan processing (which, however, are not directly reported by the banks).

The differences between the interest measurement before and after FISIM are by no means trivial, as, for example, a glance at the German national accounts for 2018 reveals: According to these statistics, private households were faced with interest expenses of EUR 52.8 billion and earned interest income of EUR 10.9 billion in that year. In contrast, the figures after taking indirect bank fees into account are interest expense of EUR 20.1 billion and interest income of EUR 29.0 billion. This means that FISIM turns net interest income that is well in the red (EUR -41.9 billion) into a sizeable surplus (EUR +8.9 billion). This shows that the method used to calculate interest has a considerable impact on the result of the calculations.

For the purposes of our analysis, to assess the impact of low interest rates on household finances, we do not believe that it makes much sense to look at interest income and expenses after the allocation of financial intermediation services indirectly measured. While this sort of break-down might be consistent with the logic behind the national accounts, in the sense that it facilitates an estimate of the contribution to added value made by the banking sector, it does not reflect the reality of life for savers in any way. After all, savers do not live in a theoretical world; they are not interested in what could have been credited to their account at the end of the year if the indirect banking services had been taken into account. Rather, they are only interested in the funds that actually end up in their account. The same applies to their interest expenses, which no saver is likely to break down into pure interest payments and fees in his head (after all, what formula would she use?). What is relevant is the amount that has to be paid to the bank every month.

Non-financial corporations – always on the sunny side

Only non-financial companies have been able to consistently benefit from the low interest rate environment (see Figure 1). On the one hand, this reflects their role as net borrowers, but on the other hand it also reflects the fact that long fixed-interest periods are hardly widespread in the lending business with companies, and that interest rate cuts can be passed on so quickly. In all countries (except for the Netherlands), interest rates were more than halved since 2008; in Spain, they dropped by 3.7 percentage points and in Portugal by a whopping 5.3 percentage points.

The extent to which companies could lower their interest burden, however, also depended heavily on the adjustment of debt levels. Spanish companies, for example, reduced their loans by almost 20%; in Italy and Portugal, debt levels remained flat over the last decade. As a result, companies from these three countries saw the biggest improvements in their net interest incomes. On the other hand, gains from lower interest rates were almost completely eaten up from rising debt levels in the case of Belgian companies, particularly in the last couple of years when net interest income started to deteriorate again.