Executive Summary

The recent gathering of central bankers at the Jackson Hole symposium of August 2019 was the occasion for prominent members of the Fed to confess a sense of powerlessness when confronted with the consequences of the White House’s disruptive economic policy. Several stylized facts suggest that the Fed is not in the driving seat of U.S. monetary policy any more.

- The Fed’s independence is at risk as President Trump’s tweets and recent institutional reforms making it more accountable to public bodies and civil society, as well as higher pressure from public opinion, have significantly increased the number of constraints weighing on its decisions. A text-mining approach, based on an analysis of sentiments on social media, confirms that 2017-2018 was a turning point with regard to the perception of its policy.

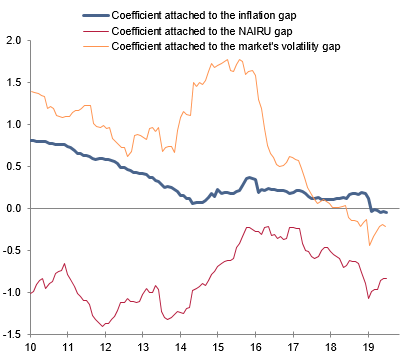

- The Fed is now too “market-dependent”. A policy reaction function with time-varying parameters shows that the Fed has increasingly attached a larger weight to the stabilization of market volatility, to the detriment of its targets on growth and inflation.

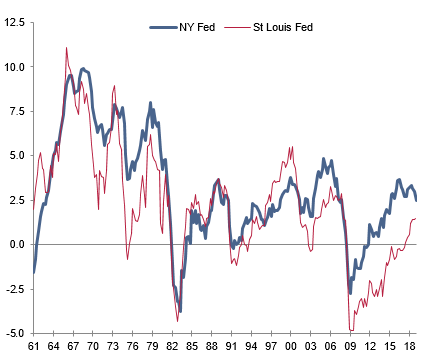

- The Fed is less and less credible in fulfilling its dual mandate. Our proprietary indicators mirror a higher risk of persistently undershooting its 2% inflation target over the medium-term, an altered capacity to maintain a situation of full employment - should the economic cycle deteriorate again - and higher risks of policy mistakes.

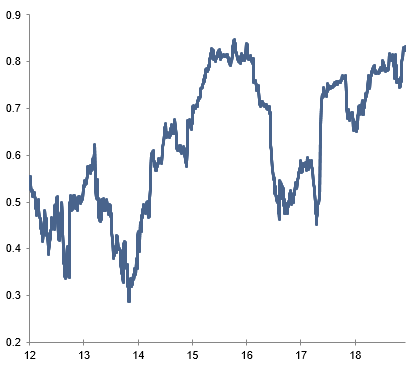

- The Fed has become a poor guide for the market. We show that cross asset correlations have reached a pretty high level in 2019. This is equivalent to a loss of directionality for the market, i.e. it suggests that the Fed has become a poor guide for investors but also shows that there won’t be any place to hide in case of a severe episode of stress.

- The Fed is about to lose its grip on currency policy. Despite an easing of U.S. monetary policy, the USD Trade Weighted index reached a record high during the summer of 2019. This primarily reflects a loss of influence on currency issues because of the actions of the U.S. Treasury and the People's Bank of China (PBOC).

History tells us that weaker central banks are associated with a higher risk of recession. Policy mistakes range from prematurely tightening monetary policy, nurturing bubbles, or lacking the authority in circumstances requiring rapid and bold moves of stabilization. Separately, the lack of direction perceived by the market is propitious to the existence of multiple equilibria and self-fulfilling prophecies. This combination of factors is prone to increase the probability of recession, as observed today.

Introduction

Today, U.S. unemployment is below 4% (maximum employment objective fulfilled) and inflation is broadly under control, close to 2%. Despite being close to its objectives, the Fed seems to be eager to ease its monetary policy in a context of high political and trade uncertainty in order to preemptively smooth an upcoming deceleration of growth. One can reasonably ask the question of a possible over-reaction of the Fed, which is possibly being influenced by the market or the U.S. government. In a context of a late phase in the cycle and increasing probability of a recession, there is a risk that a weaker Fed favors self-fulfilling phenomena and contributes to aggravate the impact of a potential correction.

The Fed’s independence is at risk due to higher pressure from external actors

Four former heads of the U.S. Federal Reserve (Ben Bernanke, Alan Greenspan, Janet Yellen and Paul Volker) recently published an article in the Wall Street Journal (“America Needs an Independent Fed”, 09 August 2019) reiterating the need for Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members to remain independent from any political pressure. Today there is a high probability that the Fed’s independence is at risk due to the following four factors:

- Direct pressure from President Trump on the Fed. A succession of tweets by President Trump has clearly indicated his strong dissatisfaction with Jerome Powell’s policy. Because of his moderation in cutting the official rate, Powell was described as an enemy of the U.S. in August 2019. This strong pressure coming from the U.S. President himself (the U.S. President nominates the Fed Chairman for a mandate of four years) undeniably endangers the independence of the Fed.

- A reinforcement of the Fed’s accountability to the public. In the years following the global financial crisis (GFC), the Fed’s accountability to the public has significantly increased. This followed criticisms that it abused its mandate by intervening in a discretionary manner to save failing banking institutions during the peak of volatility in 2009 and by injecting huge amounts of liquidity into the U.S. economic system via security purchases. Since the GFC, the tone of communication has significantly harshened during testimonies of the Chairman in front of the Congress. Moreover, the Fed has recently opted for more frequent interactions with the press regarding the orientation of monetary policy: almost on a monthly basis compared with a quarterly frequency before. The accountability of the Fed is therefore much stronger now.

- ·A re-composition of the FOMC and regulators, which is likely to reflect a higher influence from the business sector. The new regulators nominated by the U.S. President to the top of the FOMC, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) have a more pro-business profile. This has definitely increased the potential of influence coming from the corporate sector.

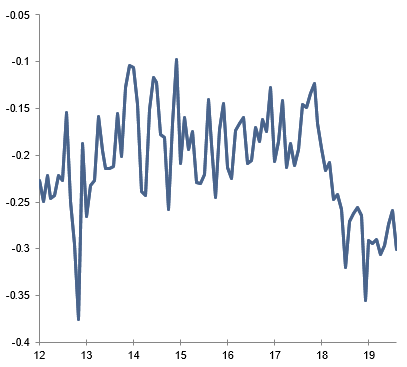

- A significant deterioration in the perception of the Fed’s action. 2017 and 2018 have represented a turning point in terms of the perception of the Fed’s action. Based on a text-mining approach[1], we build an indicator collecting words associated with negative sentiments about the Fed on social media. We can see in Figure 1 that we have recently experienced a change of regime compared with previous years in the sense that the deterioration of this sentiment is the largest and the longest-running since 2013. In a context where the Fed is being held much more accountable compared with pre-crisis times, this means that the level of pressure on FMOC members’ shoulders is very high today.