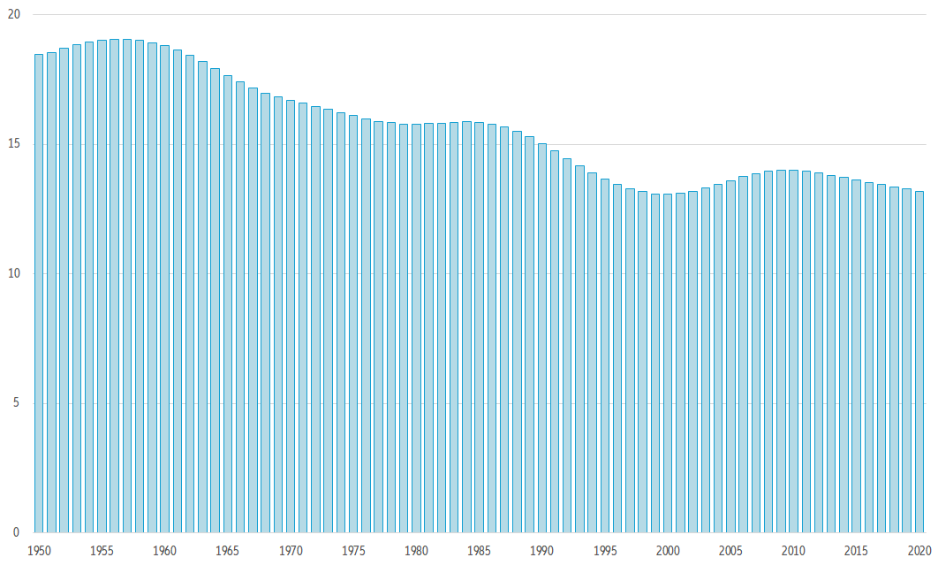

In 2020, the number of live births fell to a new record low in many industrialized countries as the Covid-19 pandemic amplified an aleady existing trend: postponing motherhood. Young women now tend to invest more time in their education and careers before starting a familiy. This behavior might result in a further decline in the total number of births and thus compound the challenges faced by already aging societies. But at the individual level, it could help narrow the income and pension gaps between men and women. In many high-income countries, the number of live births declined to record lows in 2020 as pregnancies were postponed due to the Covid-19 crisis. However, the pandemic only amplified already existing trends : Barring a few temporary interruptions, the number of newborns in more developed regions has been falling for decades, from 19.1mn in 1956 to around 13.2mn in 2020 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of births in more developed regions (in million)

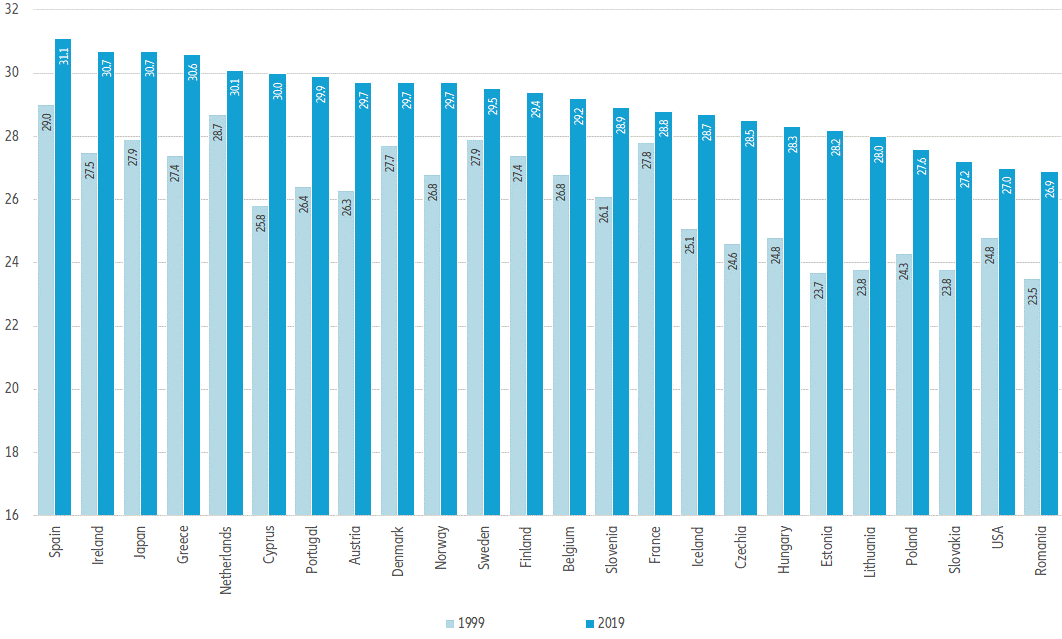

One explanation might be the increase of women’s average age at first birth: For example, during the time of the baby boom in 1960, the average age of a mother at first birth in Germany was 25.0 years. In 1999, it was 28.0 years and in 2019 it was 30.1 years . We observe similar developments in other industrialized countries: In Japan it increased from 25.4 years in 1960 to 27.9 years in 1999 and 30.7 years in 2019. In the US it rose from 21.8 years in 1960 to 24.8 years in 1999 and 27.0 years in 2019.

In the EU 27, the average age of mothers at first birth was 29.4 years in 2019, ranging from 26.9 years in Romania (partly due to a comparatively high number of teenage births ) to 31.3 years in Italy. Estonia witnessed the strongest rise of the average age of mothers at first birth: In the Baltic country it incresased by 4.5 years within 20 years, from 23.7 years in 1999 to 28.2 years in 2019. In comparison, it increased merely by one year in France, the country with the highest birth rate in the EU during this time span, from 27.8 years to 28.8 years (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average age of women at first birth 1999 and 2019, in years

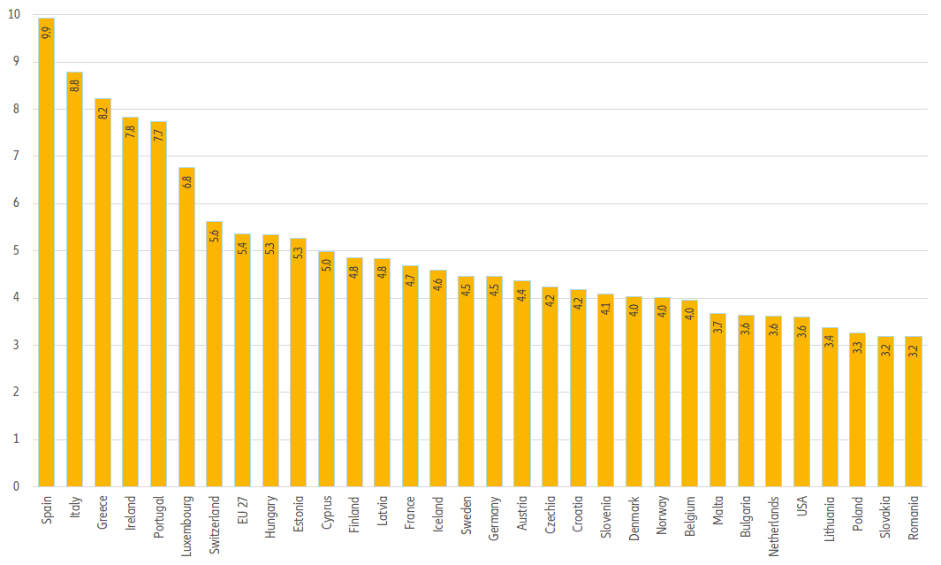

At the same time, the share of mothers aged 40 and older has also increased: In 2019, 223,278 or 5.4% of all newborn children in the EU were born to mothers aged 40 and older, and one in four were their mother’s first child (see Figure 3). Spain (9.9%) and Italy (8.8%), the countries with the lowest birth rates in the EU after Malta, reported the highest shares of older mothers . In the US the share was 3.6 % (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Share of babies born by mothers aged 40 and older 2019

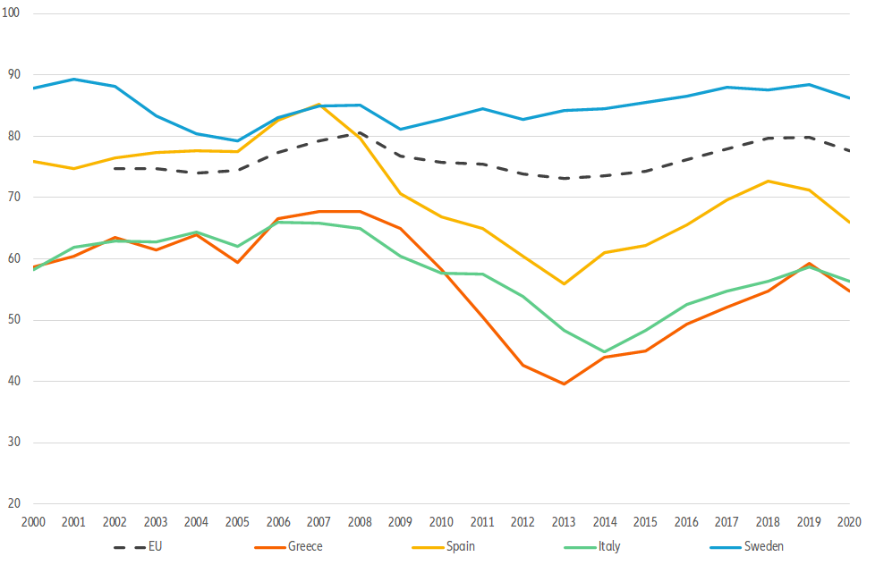

The reasons for delaying motherhood are manifold and not every late motherhood was deliberately planned. They include higher educational levels, career aspirations and progress in reproductive medicine , but also the lack of a suitable partner or stable relationship as well as the lack of a stable income. For instance, Spain and Italy also report the lowest employment rates of young people after completing their education within the EU 27 . As a consequence, young people in these two countries also start to set up their own households at a later age than their peers in other EU countries: While the average age of young people leaving home in the EU is 26.4 years , it is around 30 years in Spain and Italy. These two factors combined probably contribute to the postponement of motherhood and the low birth rates in the two South European countries (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Employment rates of young people aged 20 to 34 after one to three years since completion of highest level of education, in percentage

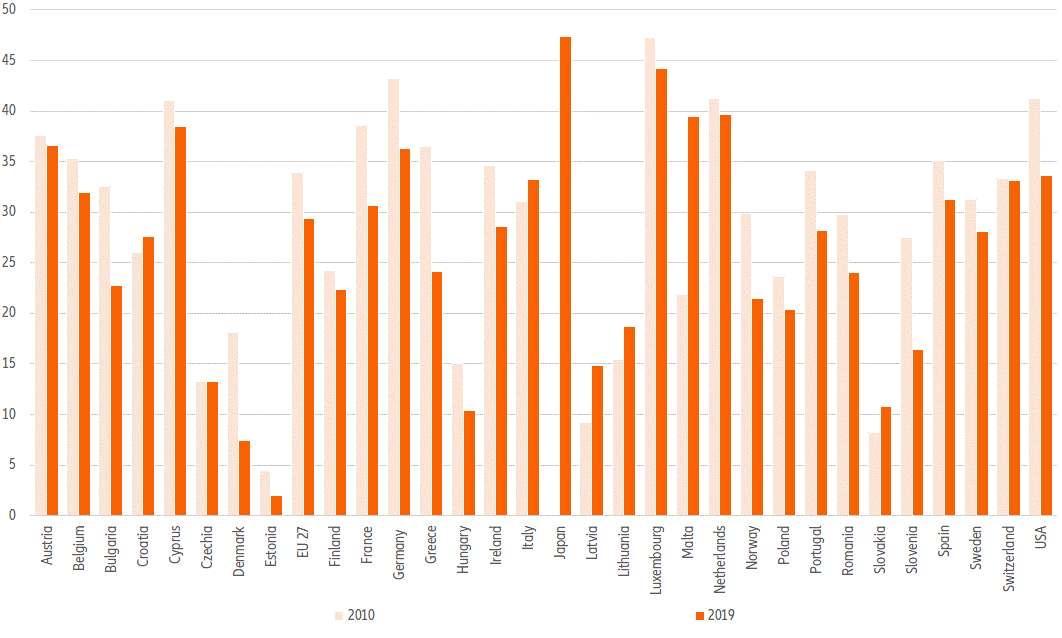

However, there is a flipside to the coin: On the one hand, the postponement of motherhood might further exacerbate the decline in birth rates and thus the aging of societies, since the older the mother is at first birth, the higher the risk that the wish for another child will remain unfulfilled or will be given up – despite the advances in reproductive medicine. But on the other hand, it can have a positive effect on the income and wealth situation of women and thus contribute to reducing the income and pension gap in the long term. The average pension of a woman aged 65 and older in the EU in 2019 was still 29.4% lower than that of her male peers and there were also still marked differences between the member countries, with the pension gaps ranging from 2% in Estonia to 44.2% in Luxembourg. Japan and the US were no exceptions to the rule: here the pension income gaps amounted to 47.4% and 33.7%, respectively. However, there has been a slight decrease in the average pension gap of 4.5pp in the EU 27 within the last decade, i.e. from 33.9% in 2010 to 29.4% in 2019 and by 7.6pp in the US, albeit since the turn of the century (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Gender pension gap 2019 and 2010, in percentage

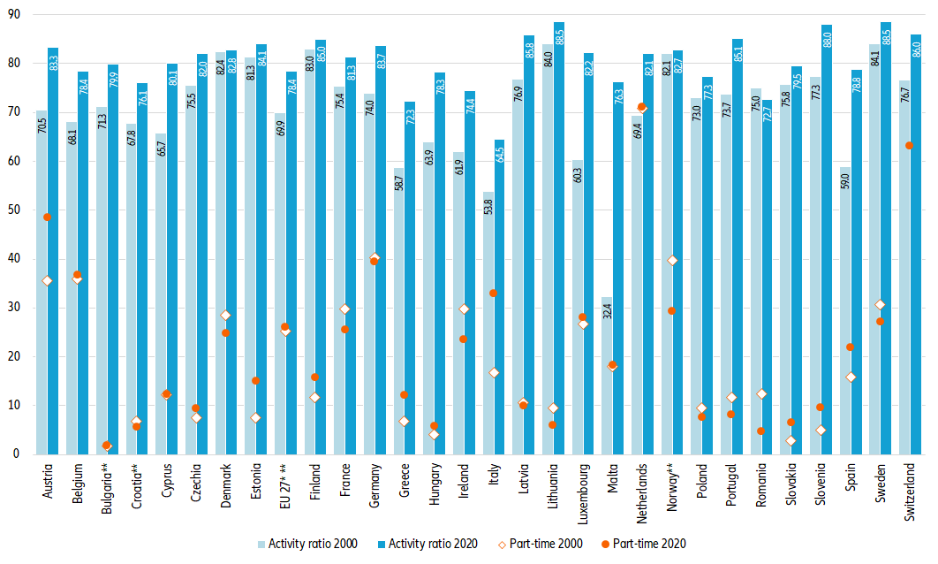

This decrease of the average pension gap reflects the increase in the labor market participation of women in recent decades. Within the EU, the activity ratio of women increased from 69.9% in 2002 to 78.4% in 2020, with the labor force participation rates ranging from 64.5% in Italy, up from 53.8% in 2000, to 88.5% in Latvia and Sweden . This is welcome progress, but it is also evident that higher activity rates alone will not close the gap. For that something else has to change: In 2020, 26.1% of all women employed in the EU worked part-time or had only a temporary contract, while the respective share among their male peers was only 6%, though with marked differences between the countries. In the Netherlands these shares were far above the EU average, with more than two thirds of all employed women but also around 20% of male employees working part-time (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Labor force participation rates of women in the EU, age group 25 to 59, in percentage

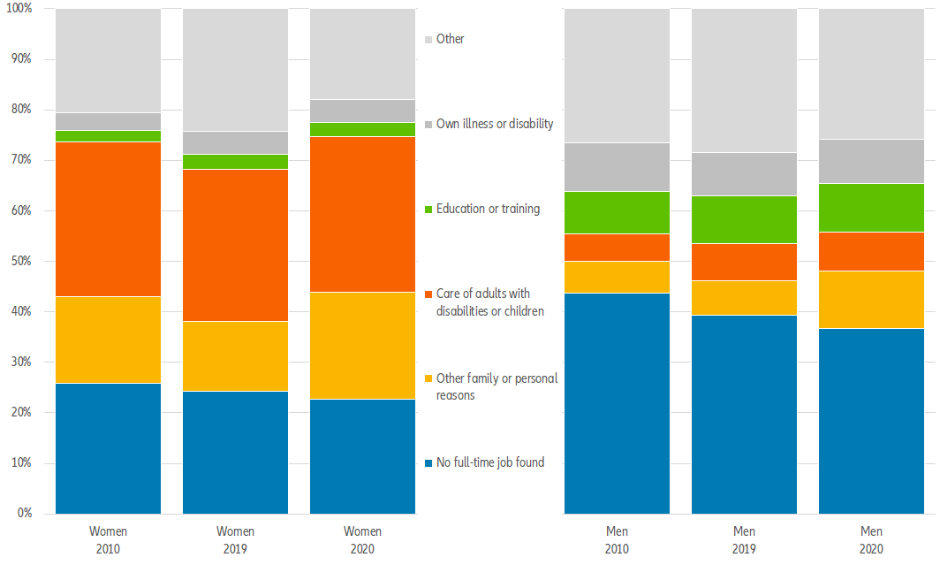

Furthermore the shares have hardly changed on average over the last decades and even increased in many countries , pointing towards the persistence of traditional role models within families: Women reduce working hours to care for an adult with disabilities or children or out of other family reasons, while men give the lack of a full time job as main reason. The Covid-19 pandemic changed these behavioral structures marginally, however it remains to be seen if these changes are permanent or only temporary (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Marked gender differences in the reasons for part-time work

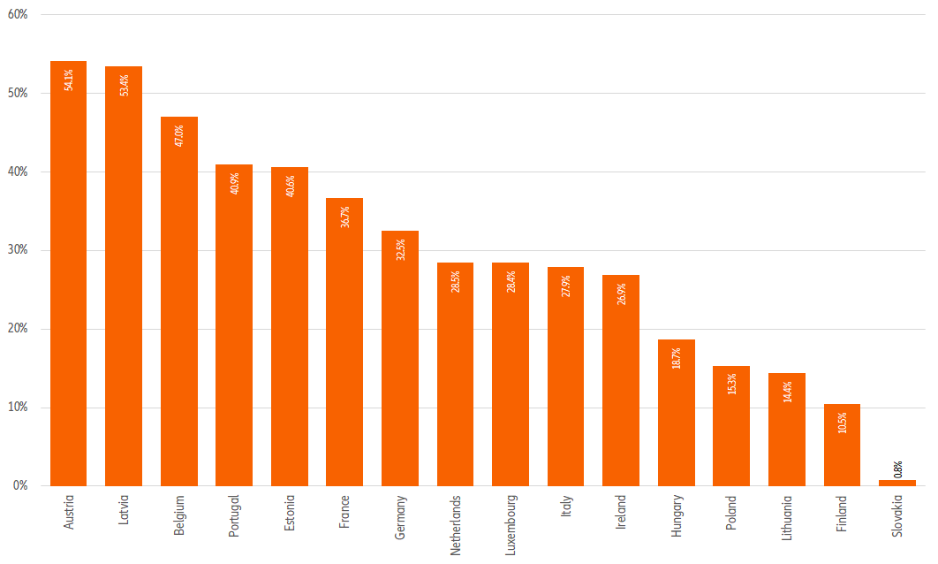

These differences are reflected in the pension entitlements of women as part-time workers or employees whose wages are below certain income thresholds are often not enrolled in occupational pension schemes. But even if women have access to retirement saving schemes, their accounts often show lower balances than those of men due to still existing income gaps and breaks in their careers. (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Gender gap in assets in all retirement savings arrangements, latest year available

These gaps are compounded by differing risk behaviors when it comes to investment decisions . As the pension gap might – at least partially – reflect different preferences in life, it is of utmost importance to adress this “investment gap”, too. Our recent

financial literacy survey showed a huge gender gap in all analyzed countries: while 36.4 % of all male respondents answered all questions related to risk literacy correctly, only 20.7% of their female peers did. This corresponds to the finding that 80% of women in Germany are not even aware of the gender pension gap. Thus, the improvement of women’s finanical literacy should be a priority, alongside facilitating access to supplementary pension schemes.