Executive summary

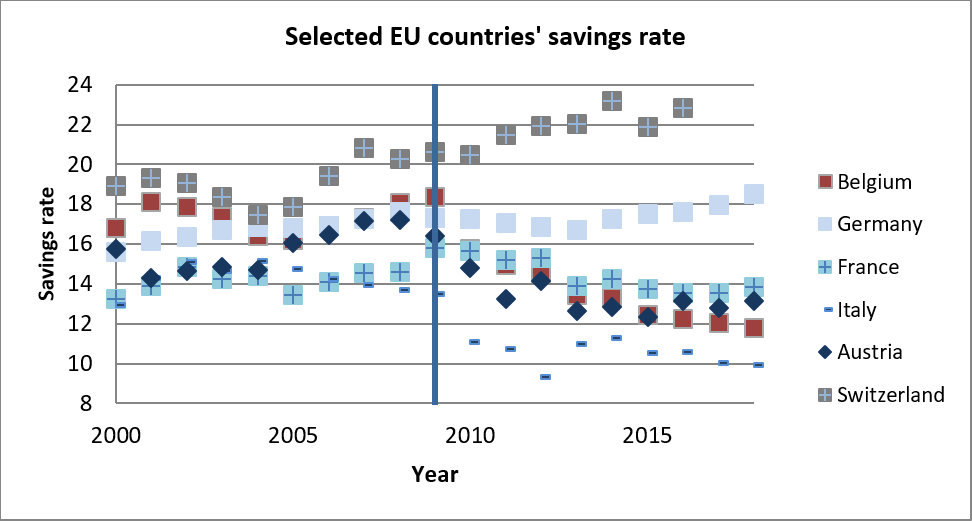

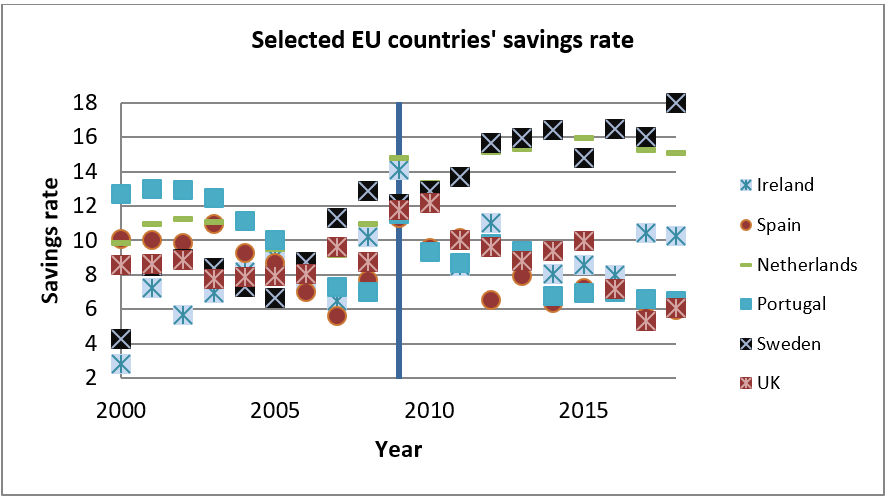

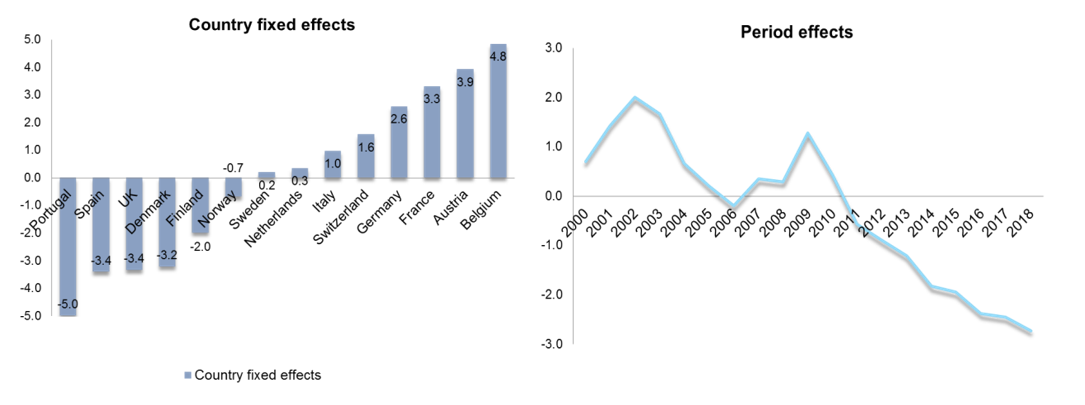

- Low or even negative interest rates can either cause households to reduce their savings (substitution effect) because of lower rewards, or to increase their savings (income effect) to maintain their financial income. Our analysis shows that for every drop by 1 percentage point in interest rates, savings rates increased by 0.2 percentage points in Europe. Using a balanced panel data sample, we assessed the savings behavior of households in 16 countries in the European Union from 2000 to 2018.

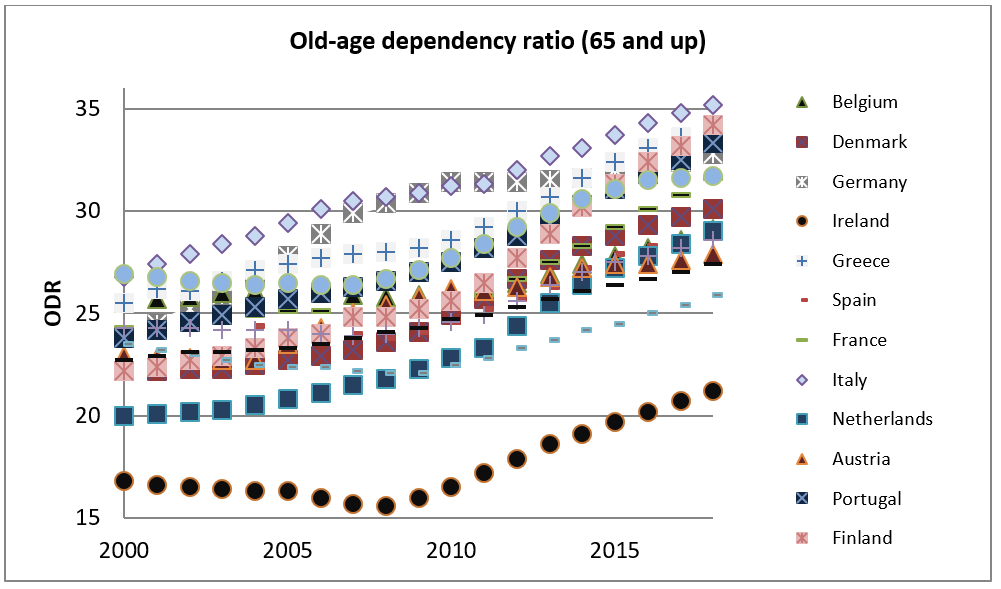

- Other factors than monetary policy have a much bigger impact on savings behavior, namely demographics (old-age dependency ratio), with an effect of 0.4pp; public social expenditures (-0.7pp) and in particular health expenditures (-1.5pp). With a rapidly aging population across Europe, prolonged life expectancy fosters continued savings, even in retirement. Secondly, a weak welfare state encourages precautionary savings. Finally, high health expenditures further encouraged to save.

- Low or even negative interest rates by themselves will not magically lead to productive savings i.e. less no-yielding deposits and more high-yielding risky assets such as equities, or real estate. An overhaul of the institutional set-up, first and foremost regarding the pension and tax systems, is indispensable for monetary policy to be more effective.

Introduction

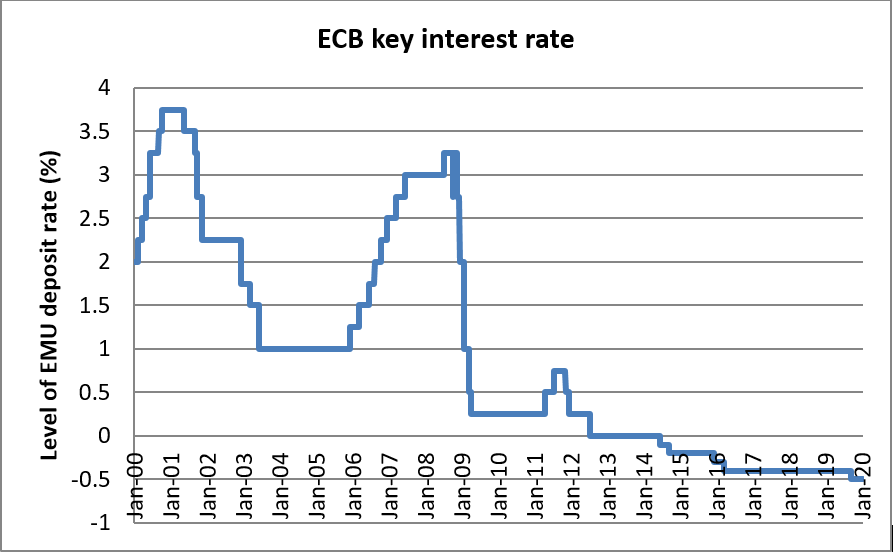

Since the outbreak of the great recession, interest rates in the developed world have fallen to historical lows. In the summer of 2014, the European Central Bank lowered its interest rates on excess bank reserves into negative territory (-0.1%). This unconventional measure to boost the economy was supposed – amongst other things – to deter households from withholding consumption today in favor of consumption tomorrow, i.e. saving. Low interest rates decrease the rewards of saving. Therefore, the obvious effect for a rational agent would be to save less because why bother if instead of being rewarded households are penalized with negative rates? Has this been the case, though? Has the European Central Bank succeeded in modifying the behavior of households? What other factors are at play? We will discuss the effects of the unconventional monetary policy on households’ savings across different countries in Europe.

Box: Life-cycle theory of consumption

The life-cycle theory of consumption is the intertemporal allocation of time, effort and money. Agents make sequential decisions to achieve a certain (stable) financial goal using the currently available information as best as they can. When it comes to money matters, agents try to smooth consumption over their lifetime, which does not mean keeping consumption constant over time, but rather maintaining a constant level of marginal utility of money.

Figure 1: income and consumption over life cycle