Executive summary

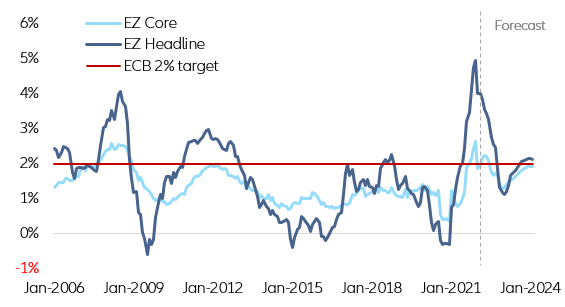

- Despite large inflation upside surprises since the last policy meeting, with the January HICP release registering the largest upside surprise ever, we think the ECB will maintain its monetary policy stance—for now. Supply-side effects, especially energy prices, are still the key inflation drivers while second-round effects—inflation expectations and wage growth—remain moderate. The ECB’s lift-off conditions for raising rates are still unlikely to be met this year, especially given the ECB’s tolerance for temporary inflation overshoots as a key result of its recent Strategy Review.

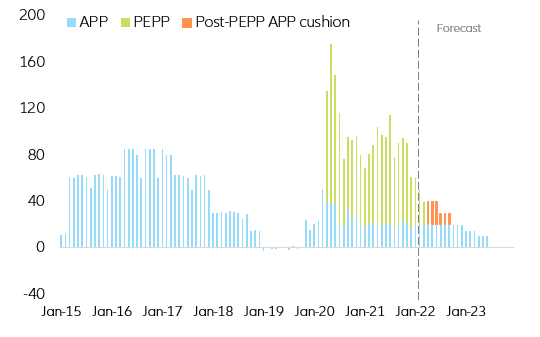

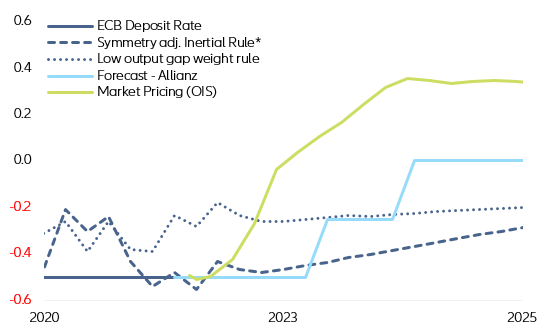

- We expect that the ECB will start “real tapering” (i.e. winding down the general asset purchase program) in January 2023, followed by a 25bps rate increase in September 2023. QE effects will limit the upside potential for long-term yields for many years. Once “real tapering” starts, it should not be interpreted as a signal that the ECB will soon loosen its grip on the term structure of Eurozone yields. Tapering is just a new phase of QE where the decisive parameter shifts from net purchases to reinvestment policy. In a three-year full reinvestment scenario, it will take 10 years before the 10-year German Bund yield will return to its long-term average of about 1.5 percent.

- However, the ECB’s current forward guidance gives little room for maneuver if inflationary pressures become more broad-based and entrenched. A hawkish policy shift might need to be quite aggressive, including inverting the current exit sequencing—hiking while continuing with QE, which could raise the risk of increasing dissent in the ECB Governing Council.

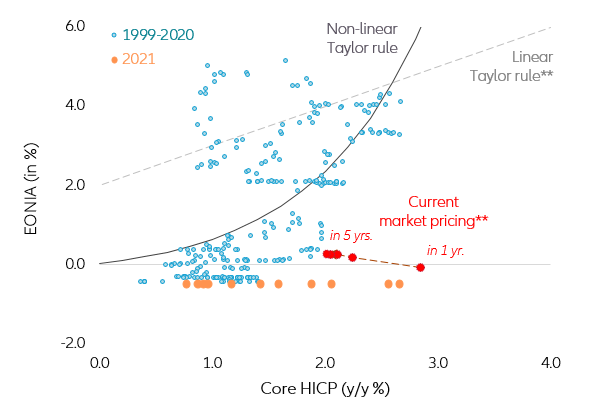

- Looking towards the medium-term beyond the current challenge of effective forward guidance, we expect the hiking cycle to be very shallow, suggesting that there will be little tightening in real terms. We see the terminal rate of 0 % by end-2025—still substantially below the natural rate. So the upcoming tightening cycle is just a phasing-out of the current crisis mode rather than a clear departure from the accommodative monetary stance.

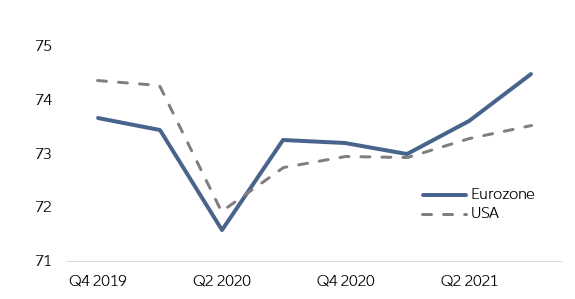

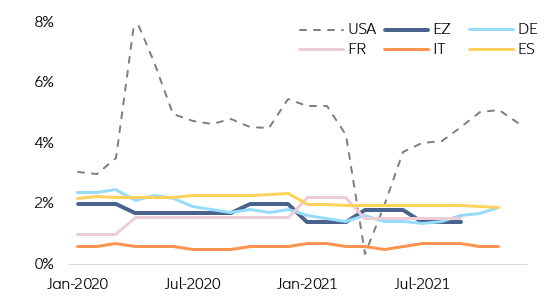

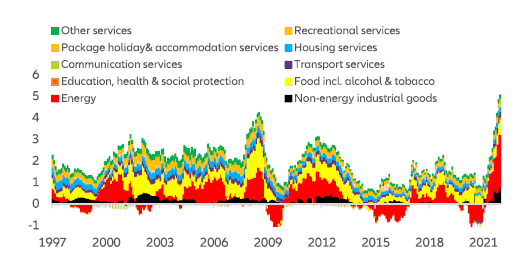

At tomorrow’s Governing Council meeting, the ECB will likely reconfirm its 2022 policy plan, increasingly standing out as a late bloomer when it comes to reigning in monetary policy support compared to the Fed (and most other central banks). Last week, the US Federal Reserve delivered a very hawkish policy meeting, with the rate lift-off announced for March (when tapering will end) and balance sheet reduction likely to follow as soon as Q1 2023. We believe that the urgency of a similarly hawish tilt is far less pressing for the ECB. Fundamentals and recent inflation dynamics help explain the growing policy divergence: The US and the Eurozone share similar drivers of current inflationary pressures, especially higher energy prices and goods supply bottlenecks amplified by catch-up demand, which boosted official core measures as prices for furniture, appliances and cars, as well as housing, have risen significantly. However, the inflation dynamics are quite different on either side of the Atlantic:

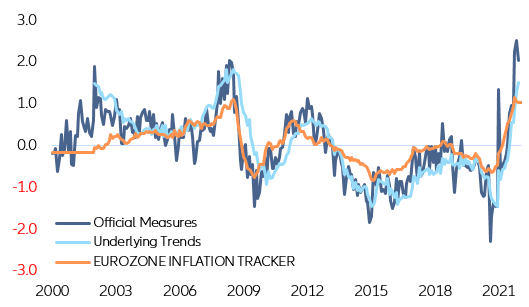

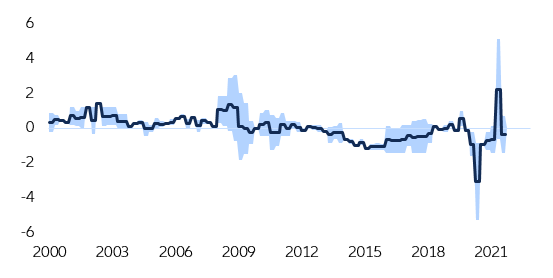

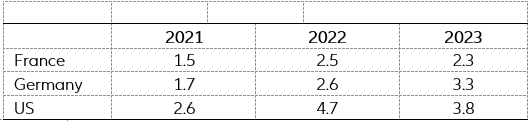

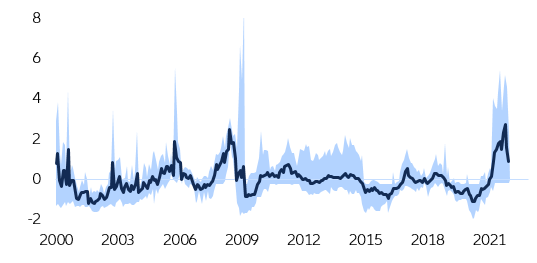

- In the US, headline inflation (as measured by personal consumption expenditure (PCE)) exceeded 7% y/y in December, more than 2pp above the consumer price index (CPI) in the Eurozone (Figure 1). Core inflation stood at 4.9% compared to 2.6% in the Eurozone, and long-term inflation expectations (measured by the 5y5y swap rate) have moved considerably more than in Europe (2.4% vs. 1.7%, Figure 1). We expect core inflation to drop further (together with greater divergence across member states in terms of non-energy core goods inflation) amid moderate services inflation (below or close to 2%).

Figure 1: Eurozone inflation – headline and core HICP (y/y, in %)