With the Covid-19 crisis, zero interest rates will become entrenched in Europe for the time being. Besides the (negative) long-term effects – rising inequality, distorted financial markets and misallocation of resources – there are also direct income effects. So far, they have resulted in the “transfer” of billions of euros from private households to the state and corporate sector. The intermediating banks, too, have suffered in the process, big time. The income effect is visible in the net interest income of sectors, which is the difference between interest income (e.g. households’ received interest from bank deposits and bonds) and interest expenses (e.g. households’ paid interest on loans) . When calculating the net interest income for the four main economic sectors – the government, households, non-financial companies and financial corporations (banks) – we use interest payments before financial intermediation services, indirectly measured (FISIM, see box below). The results for each sector in individual Eurozone countries can be replicated with the “Allianz Net Interest Income Calculator”. In the following, we discuss the results for each sector at the Eurozone level.

What is FISIM? The national accounts refer to two forms of interest income and expense: before and after "FISIM", which stands for "Financial Intermediation Services, Indirectly Measured". This is calculated by adding/deducting the indirect fees charged by banks as part of their lending and deposit business, calculated using models, to/from the interest payments actually made. In other words, the national accounts assume that interest payments consist of two components: the "pure" interest and the price for the banking service (e.g. loan processing, deposit management).

For the purposes of our analysis, measuring the impact of low interest rates on household finances, interest income and expenses after the allocation of financial intermediation services (indirectly measured) does not seem to be appropriate. While this sort of breakdown might be consistent with the logic behind the national accounts, in the sense that it facilitates an estimate of the contribution to added value made by the banking sector, it does not reflect the reality of life for savers in any way. After all, savers do not live in a theoretical world; they are not interested in what could have been credited to their accounts at the end of the year if the indirect banking services had been taken into account. Rather, they are only interested in the funds that actually end up in their accounts. The same applies to their interest expenses, which no saver is likely to break down into pure interest payments and fees in his head. What is relevant is the amount that has to be paid to the bank every month.

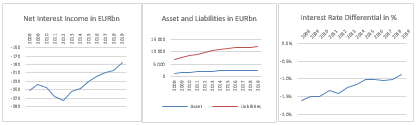

The government sector is one of the winners of the zero interest rate policy. Despite rising debt levels, the net interest income improved significantly: If annual changes over 2008 were accumulated, total savings amount to EUR195bn (2% of 2019 GDP). Given the balance sheet of governments – containing only a few interest-bearing assets but almost five times as much in liabilities – it is no surprise that its net interest income remains deeply in the red. But the improvement is nonetheless remarkable. Compared with 2008, net payments by governments (i.e. negative net interest income) have been falling by EUR70bn in the Eurozone; the turnaround since 2012, the peak of the euro crisis, is even more pronounced: it amounts to EUR90bn (see Figure 1). The decisive moment for government finances was not the beginning of the monetary easing during the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 but the “whatever it takes” speech in 2012 by Mario Draghi, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB) at that time, which ended the euro crisis and stopped the increase in interest payments of the crisis years before.

There is no doubt about the drivers behind this development. As liabilities almost doubled over the last decade the net interest income of governments was set to deteriorate, if falling interest rates had not prevented it. In fact, the fall in rates was tilted in favor of the government, as can be seen by the improving rate differential (difference between interest rates for perceived and paid interest): While the rate for perceived interest dropped by 165 basis points (bp), the rate for paid interest fell by 240bp since 2008.

Figure 1 – Net interest income and its drivers: governments, 2008 – 2019, Eurozone