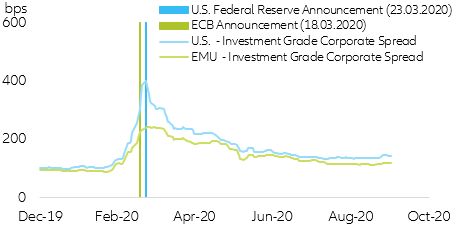

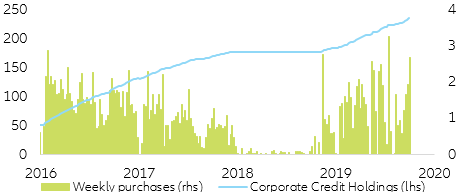

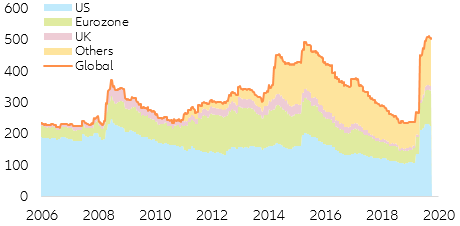

Central banks, allegedly in the front line? As the pandemic brought large swathes of the global economy to a standstill, both the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank started loading their respective policy bazookas. As soon as 18 March, the ECB announced its EUR750bn Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which included corporate credit and non-financial commercial paper in its eligible asset universe. This initial stimulus was later extended by an additional EUR600bn (Figure 1). Five days later, the Fed announced its own version of the PEPP, consisting of a comprehensive package that, by mid-April, amounted to USD2.3tn. Surprisingly, for the first time in history, the Fed included investment grade corporate credit and fallen angels in its investable universe. However, the eligible fallen angels had to fulfill certain criteria to be considered for the program, in the Fed’s wording:

“Issuers that were rated at least BBB-/Baa3 as of March 22, 2020, but are subsequently downgraded, must be rated at least BB-/Ba3 at the time the Facility makes a purchase.”

Figure 1. Central banks’ policy response

Sources: BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

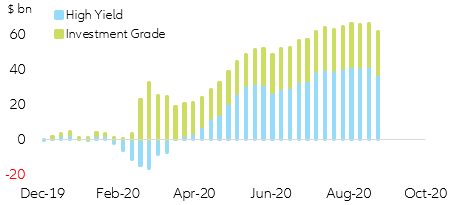

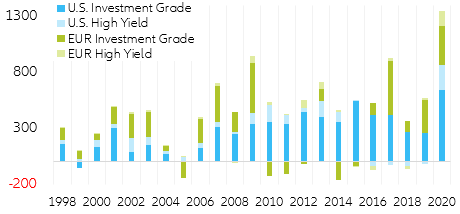

Both central banks’ decisions triggered an extreme market rotation into corporate credit (especially in the high yielding segment). But in this rush for returns, investors did not seem to care about the composition of the funds and Exchange Traded Funds they were investing in, as the most popular U.S. high-yield funds contained a big chunk of non-eligible issuers/bonds. In other words, investors were and are funding companies that, as of today, remain ineligible to be purchased by either the Fed or the ECB with the assumption that central banks will step in should things go south.

In the specific case of the U.S. high-yield corporate credit market, investors have, to date, invested twice the capital they withdrew during the peak of the Covid-19 market correction (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cumulative mutual funds & ETF U.S. corporate credit flows

Sources: Refinitiv; Allianz Research

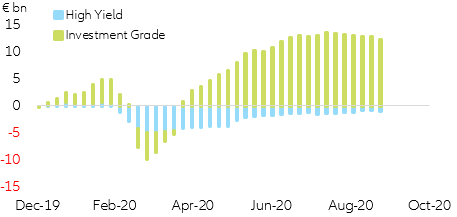

EUR corporate bond market participants reacted quite differently, likely because the ECB did not announce any inclusion of non-investment grade corporate credit into its investable universe. EUR high-yield investors timidly reinjected some capital into the high-yielding corporate credit space after the initial market shock but unlike in the U.S., the initial capital outflow experienced during the peak of the pandemic has yet to been reinstated (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cumulative mutual funds & ETF EUR Corporate Credit Flows

Sources: Refinitiv; Allianz Research

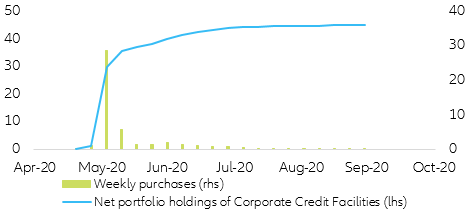

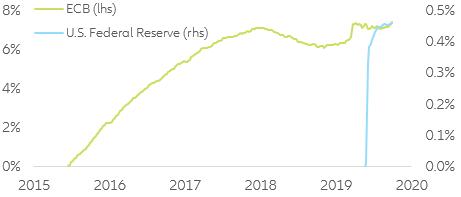

Are central banks standing by their word? In May and June, the Fed initially added ~USD40bn in liquidity into the U.S. credit market. However, ever since the end of June it has almost brought its purchases to a halt, purchasing only ~USD5bn in corporate credit from July until today. Interestingly, as of today, this market inactivity by the Fed has not brought about any major liquidity issue in the credit market, as investors seem to have taken the role of the central bank in terms of liquidity provisioning to companies (Figure 4).

Figure 4. U.S. Federal Reserve corporate credit operations ($ bn)

Sources: U.S. Federal Reserve; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

In contrast, the ECB has kept its average ~EUR2bn weekly purchases intact, adding almost ~EUR50bn extra corporate credit into its balance sheet and bringing its total corporate credit holdings to an impressive ~EUR235bn (Figure 5).

Figure 5. ECB corporate credit operations (€ bn)*

Sources: ECB; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

*Negative weekly flows due to redemptions in 2018 excluded from the chart for illustration purposes

When comparing the central banks’ interventions, it may seem that both have bought almost identical amounts of corporate credit (~USD45bn-USD$55bn) since the beginning of the crisis. Although this is true in terms of absolute size, their impact within each corporate credit market is much different. In the case of the Fed, the total corporate holdings only account for 0.46% of the whole U.S. bond market. On the other hand the ECB’s current holdings account for 7.4% of the total EUR corporate market and represent a +1.0% absolute increase from its initial pre Covid-19 holdings (6.4%).

Having said that, and taking into account that the U.S. corporate credit market is ~2.5x that of the Eurozone, (~USD8.7tn in the U.S. and ~USD3.5tn in the Eurozone), as of today the ECB has intervened with the double firepower compared to the Fed. Additionally, it can be observed that while the Fed’s participation in credit markets remains negligible in absolute terms, the ECB remains one of the biggest, if not the biggest, player in EUR credit markets.

Figure 6. Central bank’s corporate credit holdings as a percentage of the their respective corporate credit universe*

Sources: U.S. Federal Reserve; ECB; BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

*BofA Investment Grade + High Yield taken as a proxy for corporate credit universe

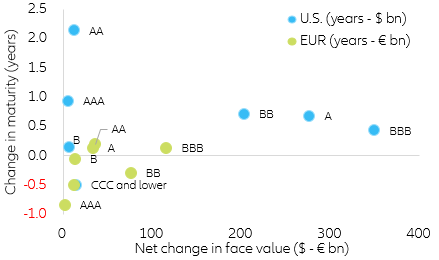

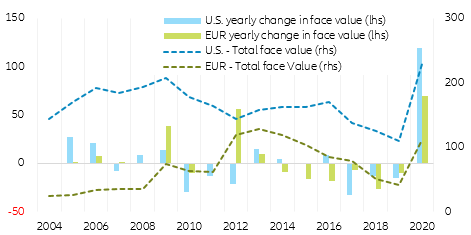

An (almost) free lunch for companies. With both central banks and market participants actively purchasing corporate credit, corporate CFOs have been provided with an (almost) free buffet for corporate debt issuance and refinancing. This is especially true in the U.S., where issuances have reached the highest amount in recorded history (Figure 7). For EUR denominated corporate credit, current issuance levels remain close to 2009 and 2017 levels but are set to surpass those previous highs by year-end. Despite this issuance dynamics difference within the investment grade universe, both markets are experiencing the highest levels of combined high-yield corporate debt issuance and fallen angel downgrades in recorded history.

Figure 7. U.S. & EUR Corporate credit change in face value ($ bn)

Sources: BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

However, while BBB & BB rated companies have remained the most active in terms of issuance in both markets, the purpose of the issuance on an aggregate level started to diverge. Even taking into account downgrades, U.S., companies have taken of the buffet by refinancing and extending the maturity of their existing debt by an average of ~0.5 to 1year. In the case of the Eurozone, most companies did not seem to jump into the market to, substantially, extend the maturity of their existing debt commitments.

In the context of maturity extension, it is really telling that unlike U.S. investors, EUR investors seem rather unwilling to enter into long-term commitments with companies spotted by rating agencies having doubtful solvency (Figure 8). However, from a global perspective, it is rather clear that most CFOs tried to take advantage of the inelastic demand for traded corporate credit (especially within the BBB and BB segments) with the main purpose of refinancing and extending their existing debt commitments.

Figure 8. U.S. & EUR Net change in face value vs Maturity*

Sources: BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

*Net change in face value contains both net issuances and rating upgrade/downgrades effect

Fallen angels – the big issuers. As seen in the previous charts, the biggest beneficiaries of the unprecedented support by central banks have been so-called fallen angels. As of today, the face value of the global fallen angel market has more than doubled, raising some questions about the long-term debt sustainability of those specific issuers (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Fallen angels total face value ($ bn)

Sources: BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

Digging deeper into both U.S. and EUR fallen angel markets, it is clear that the recent path of fallen angel debt redemptions outpacing issuances and rating downgrades has abruptly reversed. To put this into perspective, the 2020 U.S. fallen angels face value is at an all-time high and the respective EUR market is close to that of 2012.

Figure 10. U.S. & EUR fallen angels face value ($ bn)

Sources: BofA; Refinitiv; Allianz Research

Overall, central banks and investors have allowed non-investment grade companies to seek cheap funding in times of extreme uncertainty. In this context, one has to bear in mind that most of these fallen angels had almost eight to ten years of continuous economic expansion to reshuffle their balance sheets/business models so to have a convincing growth outlook that would dissipate doubts about their short- and long-term sustainability.

In this context of massive investment flows into the high-yield asset class, it is extremely important to take into account that the issuers of equity and debt markets are extremely different. Meaning that the tech-driven rally experienced in the equity market has nothing to do with that of corporate credit, as the tech sector only represents ~5-8% of the whole corporate credit market. Following this argument, the latest repetitive mantra of technology companies having a competitive edge in the future should not be applied to global bond markets.

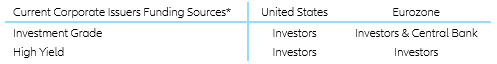

Despite Central banks’ early intervention, capital market participants remain the key players in the funding of U.S. and Eurozone corporate balance sheets, leaving the asset class at the mercy of investor sentiment and market volatility. In this context, if investors decide to withdraw their commitments to, indirectly or directly, fund corporate credit issuances (especially in the high-yield environment) central banks will have to step in decisively. Luckily enough, both central banks have the tools necessary to rapidly intervene should market participants decide to stop the cash stream. The question that remains unanswered is if central banks, especially the Fed, will wait until there is an initial wave of defaults to step in or will they be acting in anticipation of a correction. As of today, the former looks more likely, which leads to the question who or what will be the trigger for Central Banks’ decisive action in the corporate credit market?

Table 1. Corporate Credit funding sources summary

Source: Allianz Research (*Last 4 weeks for reference (<$1bn is considered inaction))