- When assessing wealth inequality and their dynamic in a globalized world, it is vital to differentiate inequalities among countries and inequalities within countries.

- The now popular narrative of ever-widening inequality is indeed only telling half of the story. It neglects the huge strides made towards better participation from a global perspective as well as the improvements within many developing countries. 1.1 billion people form the global wealth middle class today, and global concentration of wealth fell below 80%.

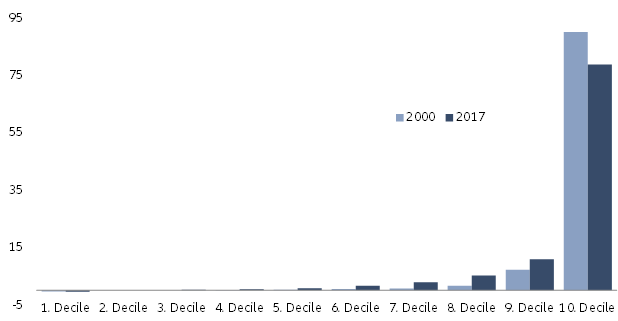

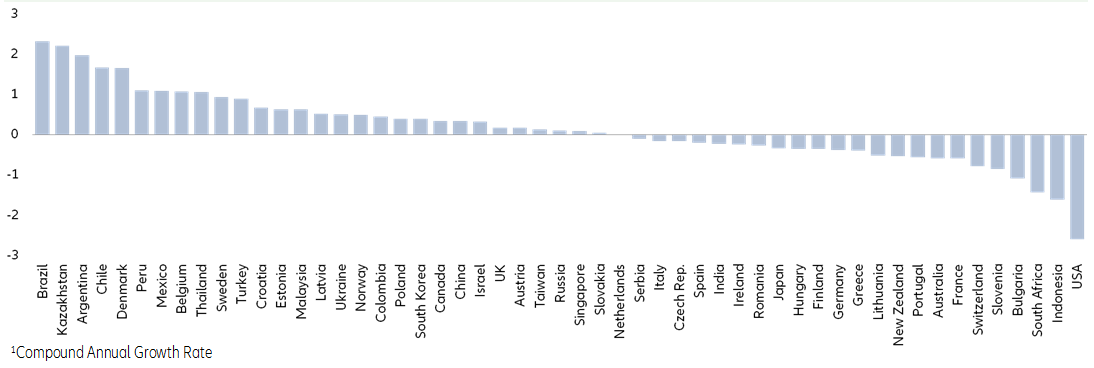

- There is no denying that wealth is still unevenly distributed at a global level – and increasingly so in some industrialized countries, first and foremost the US. This situation creates a so-called inclusive inequality paradox. More people are participating in average wealth, while at the same time, the tip of the wealth pyramid is moving further and further away from this average, and is getting smaller and smaller.

Globalization: A blessing for wealth inequality among countries

In order to analyze how wealth is distributed at global level, we have divided all individuals into global wealth classes. This classification is based on worldwide average net financial assets per capita, which stood at EUR 25,320 in 2017, more than twice as high as in 2000. The global wealth middle class ("middle wealth", MW) includes all individuals with assets of between 30% and 180% of the global average. This means that for 2017, asset thresholds for the global wealth middle class are EUR 7,600 and EUR 45,600. The "low wealth" (LW) category, on the other hand, includes those individuals with net financial assets that are below a EUR 7,600 threshold, while the term "high wealth" (HW) applies to those with net financial assets of more than EUR 45,600.

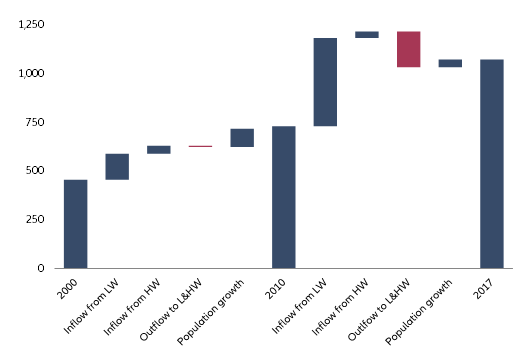

The last two decades of rapid globalization have given rise to a new global wealth middle class, which includes almost 1.1 billion people in the countries we have analyzed. Fewer than half a billion people belonged to this group at the turn of the millennium, with just under half of them coming from Western Europe, North America or Japan. Today, these countries account for only a quarter of the global wealth middle class. In contrast, China's share has soared from just under 30% to over 50% in this period. There is therefore little doubt about what the driving force behind the new global middle class is: its emergence primarily reflects the rise of China.

The figures accompanying this success story are impressive. Around 500 million Chinese people have moved up to join the ranks of the global wealth middle class since 2000, and over 100 million more can now even consider themselves part of the global wealth upper class. That means that China accounts for about 80% of movements between wealth classes since the turn of the millennium. China's rise gained further momentum after 2010, in the post-financial crisis era, which was due not least to the fact that asset growth elsewhere was somewhat weak during this period. This ultimately caused the wealth middle class in the "old" industrialized countries to grow as well, although here the trend was the other way around: about 60 million people joining the middle class have moved down the scale, i.e. as households that have been "relegated" from the high wealth class. This affects primarily the US and Japan, but also European countries such as Italy, France and Greece.

Figure 1: Change in global wealth middle class, in million