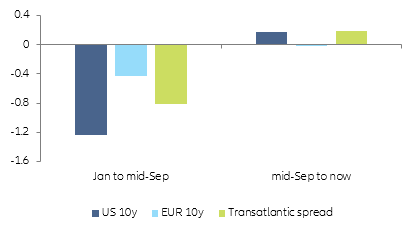

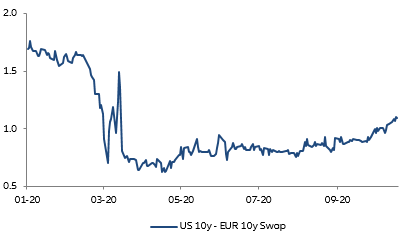

The transatlantic yield spread between the U.S. and the Eurozone narrowed by 81bp until mid-September but has re-widened by 20bp lately. In the first phase of the Covid-19 crisis, nominal yields in the U.S. and the Eurozone showed a common downward trend responding to the expected deflationary shock and coordinated monetary easing. With the Fed making full use of its greater scope for lowering interest rates (Fed funds upper bound cut from 1.25% to 0.25%), the transatlantic spread had narrowed by 81bp for the 10y maturities by mid-September. Now, a diverging trend in U.S. and Eurozone nominal yields arises, especially for longer maturities. Since mid-September, U.S. 10y nominal yields have increased by almost 20bp. In the Eurozone, they remained stable at best (10y swap rate). Accordingly, the transatlantic spread has widened by 20bp, using the EUR 10y swap as the Eurozone benchmark (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1 – Changes of 10y nominal yields and transatlantic spread (in %)

The economic momentum is in favor of the U.S. as the Eurozone is heading for a double dip. The prevailing view among market participants seems to be that this divergence in nominal yields reflects a divergence in economic momentum. Indeed, with the increasing pandemic risk and the subsequent containment measures, the Eurozone should fall back into recession in Q4 2020. We expect real GDP to decline again in France (-1.1% q/q) and Spain (-1.3% q/q), among others. This weakness in the Eurozone could even continue into Q1 2021 as we see a rising risk of a stimulus gap. Political tensions in some member states (fragile majorities, fragmented political system) may make it difficult to maintain adequate fiscal measures. In addition, there is uncertainty about the timing and extent of the payments from the EU recovery fund. Its disbursements could be strongly politicized, given the degree of Eurosceptic views in some countries. In the U.S., on the contrary, expectations are for a new stimulus as market participants seem to be positioning themselves for a Democratic victory in the presidential election.

Figure 2 – Evolution of the transatlantic spread (in %)

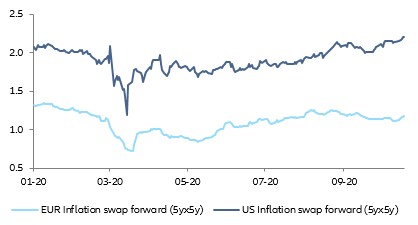

We find that the recent widening of the transatlantic spread is due to inflation expectations, more precisely to a repricing of the inflation risk premium in view of the Fed’s average inflation target (AIT). If economic momentum really was the main driver of the recent transatlantic yield divergence, one would expect rising real yields in the U.S. and somehow stagnating real yields in the Eurozone. However, by decomposing the nominal yields into the real yield and the market-based inflation expectation (inflation swap), we observe that for the 10y maturity real yields in the Eurozone have indeed stagnated since mid-September, but declined by 10bp in the U.S. This is due to a significant increase in market-based inflation expectations, which nominal yields only partially followed. Thus, the recent widening of the transatlantic spread is not explained by the real yield component but the inflation expectation component (Figure 3).

Now we want to ask ourselves: Is it due to a new anchor of long-term expectations or to higher uncertainty about future deviations from these long-term expectations (inflation risk premium)? To answer this, we need to break down marked-based inflation expectations. We use an adaptive expectations algorithm (Allais transformation) to determine the long-term expectations component and define the inflation risk premium as an uncertainty measure associated with these expectations. This decomposition shows that the recent upward trend in market-based inflation is not due to a re-anchoring of long-term expectations: these remain unchanged in the U.S. and the Eurozone. The movement is explained by the development of the inflation risk premium.

Figure 3 – Evolution of market-based inflation expectations (in %)

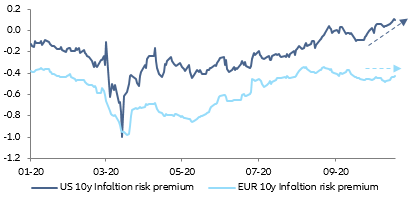

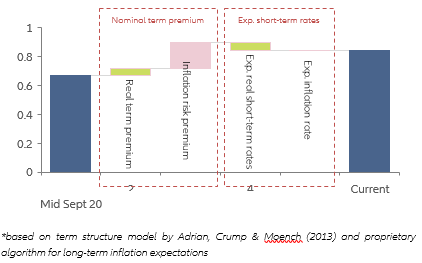

In the U.S., the inflation risk premium has risen by 18bp since mid-September. It is thus responsible for almost the entire upward movement of nominal yields we have seen during that period. In the Eurozone, the inflation risk premium remains stable (Figures 4 & 5). We think the reason for this repricing of the inflation risk premium in the U.S. is the redesign of the Fed’s inflation target. Moving to an average target (AIT) actually implies the possibility of longer periods of inflation overshooting. Market participants therefore need to price in higher inflation uncertainty, i.e. reassess the risk of deviation from their long-term inflation expectations.

Figure 4 – Evolution of inflation risk premium (10y maturity, in %)

The transatlantic spread could continue to rise up to 140bp in the coming months. Structurally, the Fed’s AIT exerts a steepening effect on the U.S. yield curve via the inflation risk premium. It could rise further the more volatility the realized inflation is going to exhibit. For the transatlantic spread, this represents a widening tendency. In the coming months we think it is quite possible that we will see levels of 140bp again for the 10y maturity, especially since currently the real yields do not yet price in a noticeable divergence in growth momentum. If the first release of U.S. GDP in Q3 comes in above expectations and/or a stimulus package is passed before the election, we could see a timely repricing here.

Figure 5 – Decomposition of the recent rise of U.S. 10y yield (in %)*

Naturally, the difference in the impact of QE on the nominal yields remains the most important factor to explain the transatlantic spread. Would a symmetrical inflation target by the ECB narrow the transatlantic spread? Some upwards repricing of the inflation risk premium would be likely. But the magnitude of this should be limited, at least for the time being, as the scenario of an inflation overshoot in the Eurozone is less credible when viewed from the past. However, the main factor for the transatlantic spread remains the extent of QE and the compression of the nominal term premium. Here the ECB is more aggressive than the Fed. For the 10y maturity, we currently estimate the compression at 185bp in the Eurozone vs 130bp in the U.S. As long as this difference persists, the structural tendency for the transatlantic spread is set for more divergence.