Sources: IHS, Euler Hermes

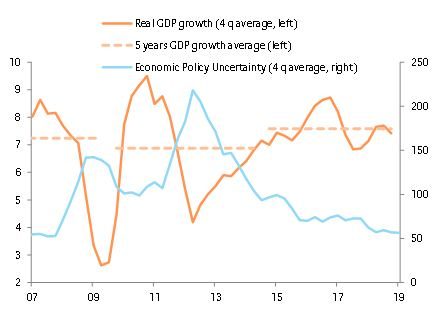

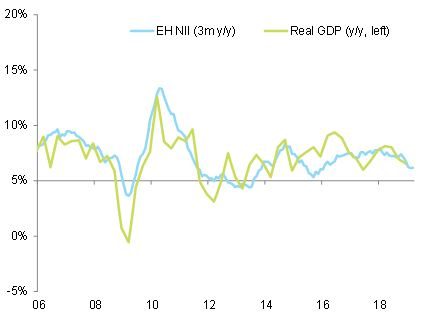

Looking ahead, we see mixed prospects for the Indian economy. On one hand, risks of policy mistakes have re-emerged over the last fiscal year as the government loosened fiscal discipline and increased pressure on the central bank to support the economy (thus threatening its independence). Externally, global demand growth is projected to slow to +2.9% this year (compared to +3.1% in 2018) and domestically, private consumption shows signs of weakness. Passenger vehicle sales, for instance, declined by -3% in March 2019.

On the other hand, the Indian economic model is still well positioned to take advantage of the next cycle. Lower oil prices (projected at USD67 per bbl on average over 2019-2022) could lead to a reduction of the merchandise trade deficit and inflationary pressures, which should support private consumption. Moreover, a trade diversion (as a result of the China-US trade spat and increasing costs in China) and the servitization of manufacturing and global trade (the delivery of a service component as an added value when providing products) provide opportunities for Indian exporters. Assuming that India makes good of this opportunity, the economy could reach the size of Germany (USD4tn+) by 2025.

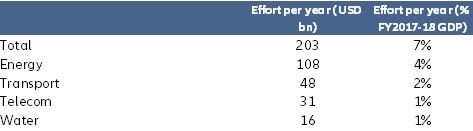

By the end of May 2019, India will have a new government that will run the country for the next five years. This provides the chance to adjust policy settings to focus on openness, infrastructure and strengthening private consumption to ensure stronger and sustainable growth over the longer term.

Openness to attract needed capital and unlock trade potential.

While the Modi administration has already made efforts to open the market to foreign capital (relaxation of foreign investment rules in crucial sectors such as defense, telecom, some e-commerce activities for instance), there’s still a long way to go to address financial shortcomings and provide opportunities abroad. Financial resources are limited as public debt is high (general government debt at around 70% GDP), the banking sector is constrained by high non-performing assets (system-wide gross non-performing assets ratio rose to 11.2% in FY2017-18) and savings are too low compared to investment, resulting in a current account deficit. Maintaining the pace of reforms will be important to continue to draw investors’ attention and maximize country’s potential. With an investment productivity of 3 (i.e., 3 units of capital are needed to create 1 unit of GDP) and a credit intensity of 1.4, India’s potential returns on investment are higher than those in China (which scores 6 and 3, respectively).

Opening the market will have three benefits: One will be to allow the government to focus on improving the creditworthiness of the public sector and banks as other actors take the baton to finance growth. Two will be a more efficient allocation of financial resources in the economy by introducing and promoting competition. Three, the move will provide a second wind to domestic demand as foreign capital will boost investment and further competition will make goods cheaper for consumers. Lower transaction costs would also boost trade, which would boost GDP growth. Research from Berg et al shows that a +1pp increase in exports growth is associated with a +1/5pp point increase in economic growth. Against this background, we see two potential categories of winners among corporates:

- Private Banks and investors: With gross non-performing assets at 4.7%, private domestic banks are the best positioned to become the main source of financing. Foreign and domestic private investors could be the next to step in.

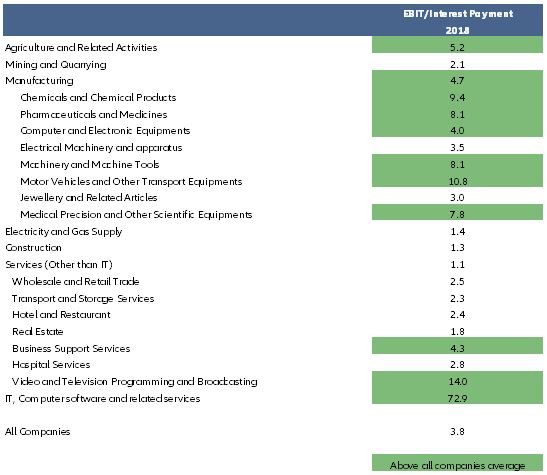

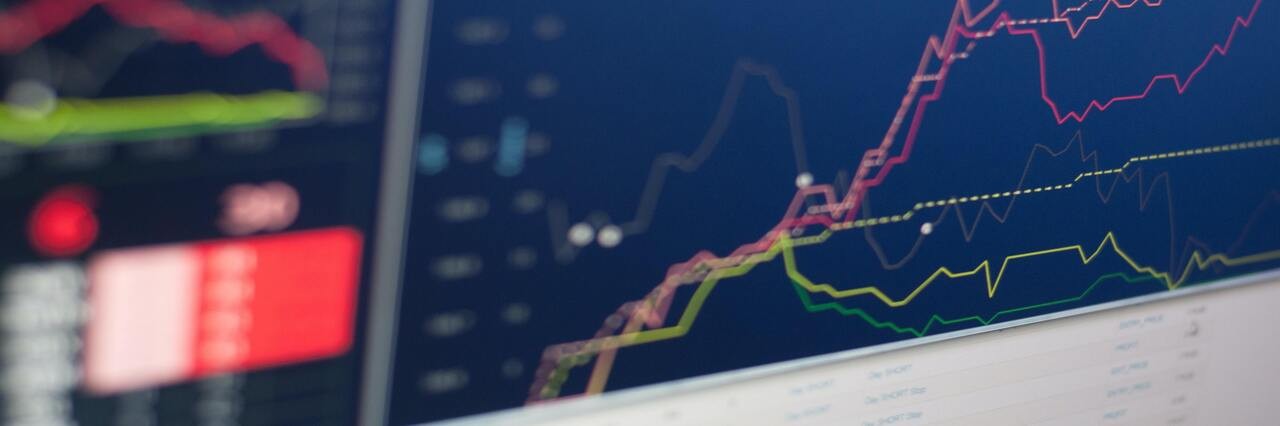

- Export-oriented companies (manufacturing and services): The first sectors to benefit will be those that already have strong financial buffers. Figure 3 shows the interest coverage of key sectors of the Indian economy. Among the tradable sectors we see business support services, IT services, moto Vehicles, chemical and pharmaceuticals as the main winners. The Indian economy is already well positioned for services exports, which account for 11% of GDP, compared to 6% in China.

Financial opening should be accompanied by a signification reduction of protectionist measures in order to boost trade as foreign companies still struggle to access the market. India’s tariffs are among the highest in the world (e.g., 13.8% simple average Most Favored Nation applied, compared to 9.8% for China in 2017) and state interventionism is also high with substantial subsidies (food-security program, for e.g.) and strong involvement of the government to protect local players (ban on foreign investments into multi-brand retail). Such persistent protectionism keeps investors away and maintains inputs costs at high levels. It has also, more importantly, led trade partners such as the U.S. to retaliate, which is a drag on Indian exporters’ sales.

Figure 3: Interest coverage ratio for listed Non-Government Non-Financial Companies