EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

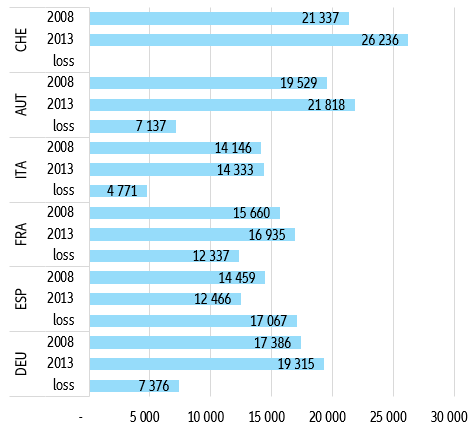

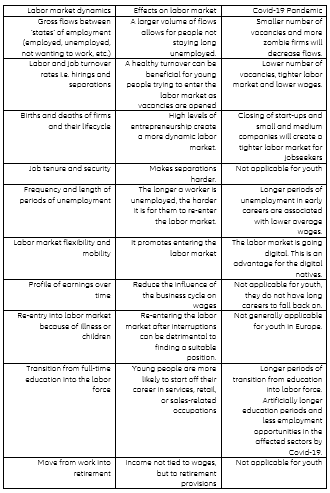

- The youth labor market is highly sensitive to economic cycles, with young people more likely to be in precarious employment than any other age group. After the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, it took years to recover across Europe, though youth incomes never went back to pre-GFC levels in Spain. We estimate that the 5-year accumulated losses were higher for youth in Spain than the annual net median income pre-GFC (PPP 17,067 or 118% of 2008 net median income). In France, we observed the second highest accumulated losses (PPP 12,337 or 79% 2008 net median income) due to high pre-GFC income growth for this age cohort. Other countries had more “demure losses” (ITA: PPP 4,771 or 34% of 2008 NMI; AUT: PPP 7,137 or 37% of 2008 NMI; DEU: PPP 7,376 or 42% of 2008 NMI). Pre-crisis net median incomes were reached in Germany and Switzerland in 2011, while France recovered until 2012 and Italy in 2016.

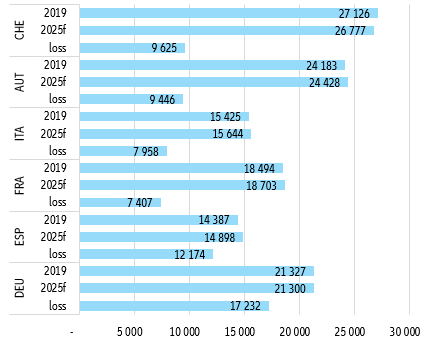

- It could take even longer to recover from the impact of Covid-19, especially in Switzerland, Austria, Italy and Germany. By forecasting the net median income for 18-24 year olds and calculating the five-year cumulative losses, we find that Spain (PPP 12,174 or 85% of 2019 net median income) and France (PPP 7,407 or 40% of 2019 median income) will have lower losses compared to the pre-Covid-19 trend only because of their meager pre-crisis growth. But for all other countries, the impact of the pandemic far exceeds that of the GFC: CHE: PPP 9,625 or 35% net median income, AUT: PPP 9,446 or 39% of 2019 net median income, ITA: PPP 7,958 or 52% of 2019 NMI and DEU: PPP 17,232 or 81% of 2019 NMI. It could take until 2024 for net median income levels to return to pre-crisis levels in most countries, but Germany and Switzerland might take an extra year to recover due to higher pre-covid income growth.

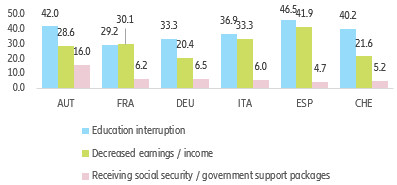

- With education also disrupted, especially for youth in Spain (46.5%), Austria (42%) and Switzerland (40.2%) , the pandemic will hinder human capital accumulation, punishing young workers further and widening already present intergenerational inequalities. This calls for policymakers to expand support programs focused on the youth, and support workers though this adjustment with (re)training and (re)skilling to avoid “job scarring”, whereby young people are pushed into long-term unemployment, with consequences for the economic recovery.

THE EXPERIENCE FROM THE GREAT FINANCIAL CRISIS

The youth labor market is highly sensitive to economic cycles as young people’s incomes are less dependent on unobservable factors such as career tenure or their earnings profile. Therefore, when a crisis hits, it starts with the young.

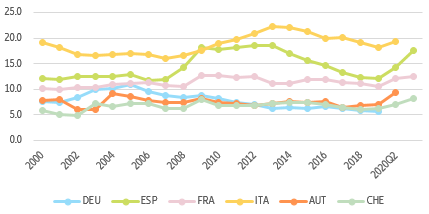

After the GFC, the 18-24 age cohort was the most affected in terms of net median income. In Germany, this group suffered two consecutive years of losses and did not see a return to pre-crisis levels until 2011 (PPP 17,933). If their income had followed the pre-GFC trend, they would have accumulated an extra PPP 7,376 or 42% of 2008 net median income (see Figure 1). In Spain, the GFC came along with the burst of the Spanish housing bubble and it hit Spanish youth hard: the pre-crisis net income was PPP 15,281 and has yet to go back to that level: we calculate the five-year accumulated losses in income to be PPP 17,067 (118% of 2008 net median income). As of 2019, the median annual income stood at PPP 14,387.

In France in 2009, the 18-24 age cohort was the only one to see median income decrease (-2.7% y-o-y) and it was not until 2012 that it recovered. When estimating the trend post-GFC versus the trend before the GFC, we find that French youth lost PPP 12,337 (79% of NMI) over a five-year span. In Italy, the effects of the crisis were felt until 2010 when the median income of 18-24 year olds decreased by -3.6%, by far the largest decrease of all age cohorts. The Italian pre-GFC income trend was not very high, thus the accumulated loss versus trend was PPP 4,771 (34% of NMI) and the median income recovered to pre-crisis levels in 2016. In Austria, the net income of the young did not slump after the GFC but it more or less stagnated during the following decade (+1.9% ten-year compound annual growth rate) Nevertheless, compared to the pre-GFC trend, youth in Austria lost PPP 7,137 (37% of NMI). In 2008, Swiss youth were once again the only age cohort that saw less money in their pockets (-1.2% median income growth y-o-y). Nonetheless, their median income recovered quickly and the rebound offset the losses caused by the GFC.

Figure 1: The path to recovery

Net median Income for 18-24 year olds post GFC in PPP and cumulative losses compared to pre-crisis trend