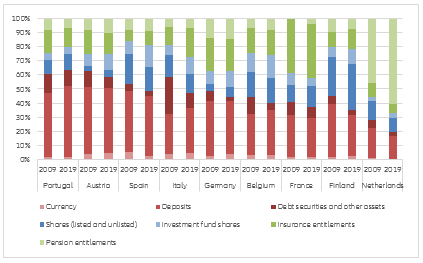

French and German savers have many things in common: Their level of financial assets per capita is similar and its development over the last decade has been almost identical. There is, however, one striking difference: The return on financial assets is way higher in France, reflecting different portfolio compositions. The consequences for consumption are substantial, resulting in a "shortfall" of around EUR800bn in consumption in Germany over the last decade, or at least around 5% of annual consumer spending.

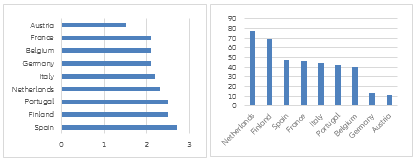

The wealth gap in Europe has widened in the last decade. Household assets have grown faster in the richer countries – above all in the Netherlands – while southern European countries are lagging behind in terms of both wealth levels and growth (see Figure 1). Looking at France and Germany, in 2019, per capita financial assets in France were EUR84,320, just above EUR77,310 in Germany. Growth rates since the Great Financial Crisis have also been very similar: +4.3% per year in Germany compared to +4.2% in France. This puts both countries in the midfield in Europe, well ahead of Portugal and Spain but also well behind the Netherlands and Belgium.

Finland is the exception to the growing divergence: In 2019, it had almost caught up with Italy, reflecting an impressive pace of growth; back in 2009, per capita financial assets of Finnish households were still nearly EUR19,000 below those of Italian ones.

Figure 1 – Financial assets per capita*, in EUR and CAGR 2010-2019 in %