EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- As the Covid-19 crisis upends our societies, we at Allianz decided to check the pulse of savers in Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Switzerland and the U.S. We commissioned Qualtrics, an experience management company, to survey a representative sample of 1,000 people in each of the seven countries about their experiences with income, consumption, savings and investment, financial literacy and risk during the Covid-19 pandemic. Additionally, we asked about their plans after the pandemic. The survey was conducted from 28 September to 21 October via an online questionnaire.

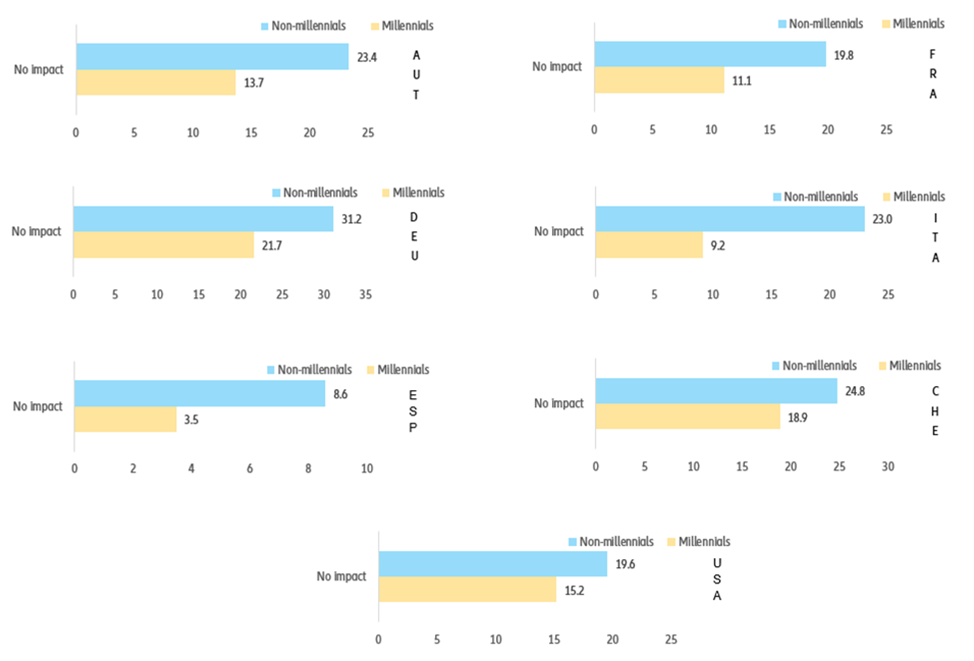

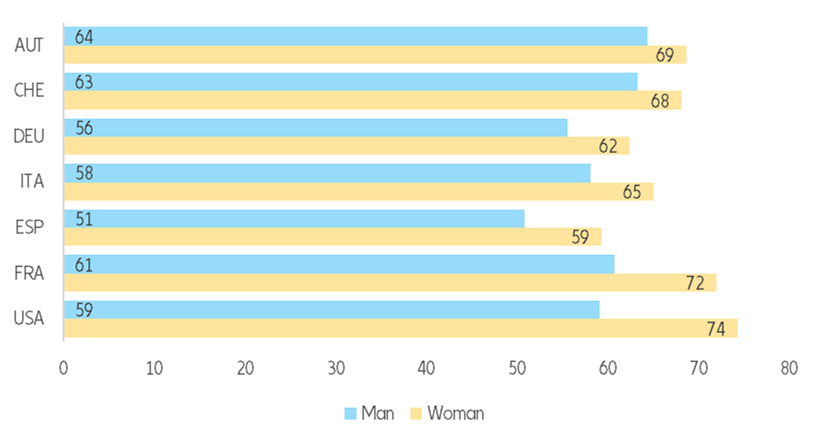

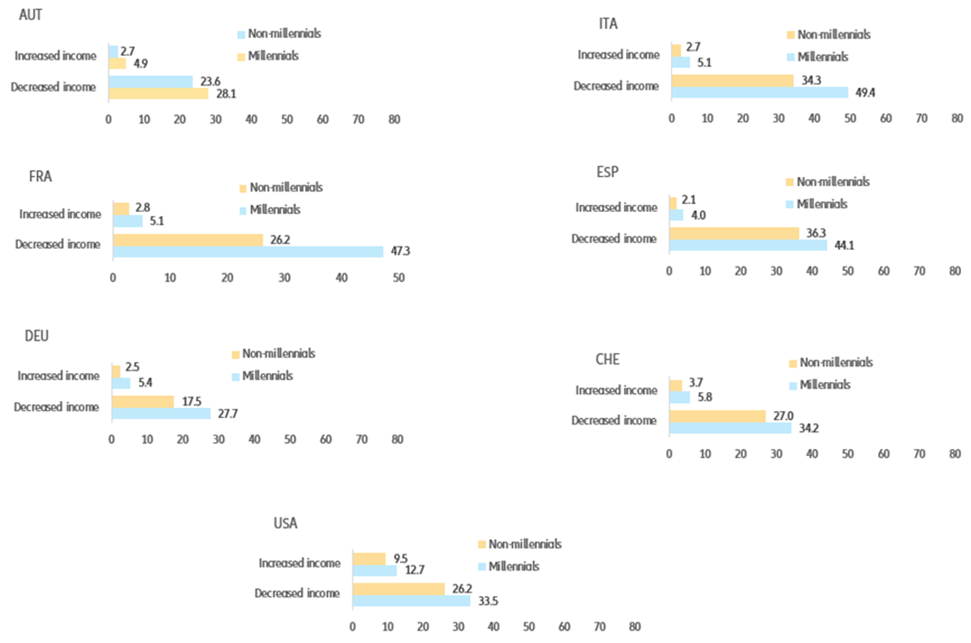

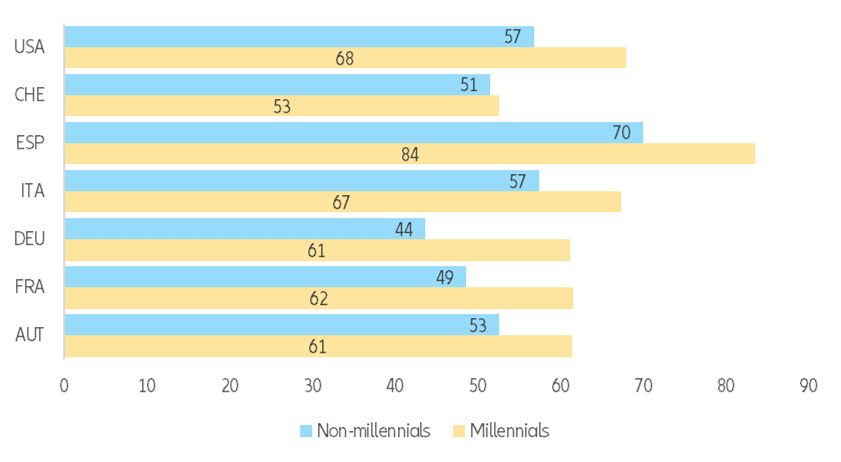

- At least 55% of the respondents in each of the seven countries reported the pandemic to be the most impactful economic event of their lifetime. Differences between the countries mainly reflect the depth of the sanitary and economic crisis, with German respondents showing the highest level of resilience. Only 20.0% of them reported having lower income because of the pandemic (against 30.0% for the total sample). There are, however, two aspects all countries have in common: women and millennials have been disproportionately affected by this crisis. 37.8% of millennials against 27.2% of non-millennials had to cope with lower income. The gender gap is equally large: 32.7%% of female respondents saw a significant drop in their income against 27.1% of male respondents.

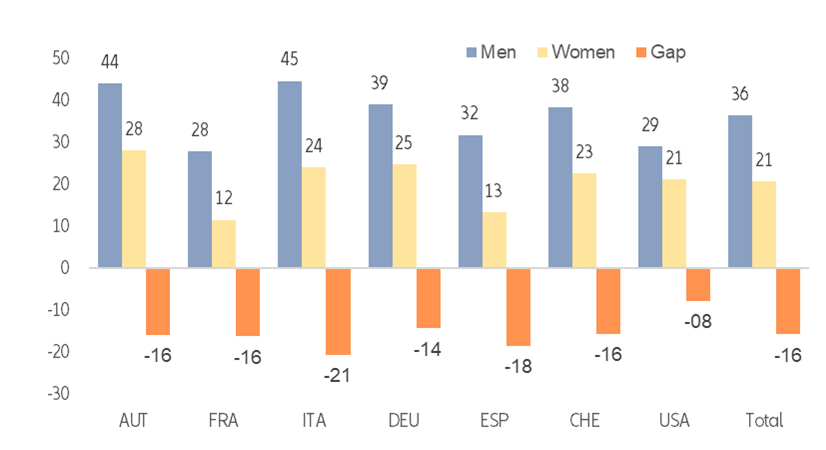

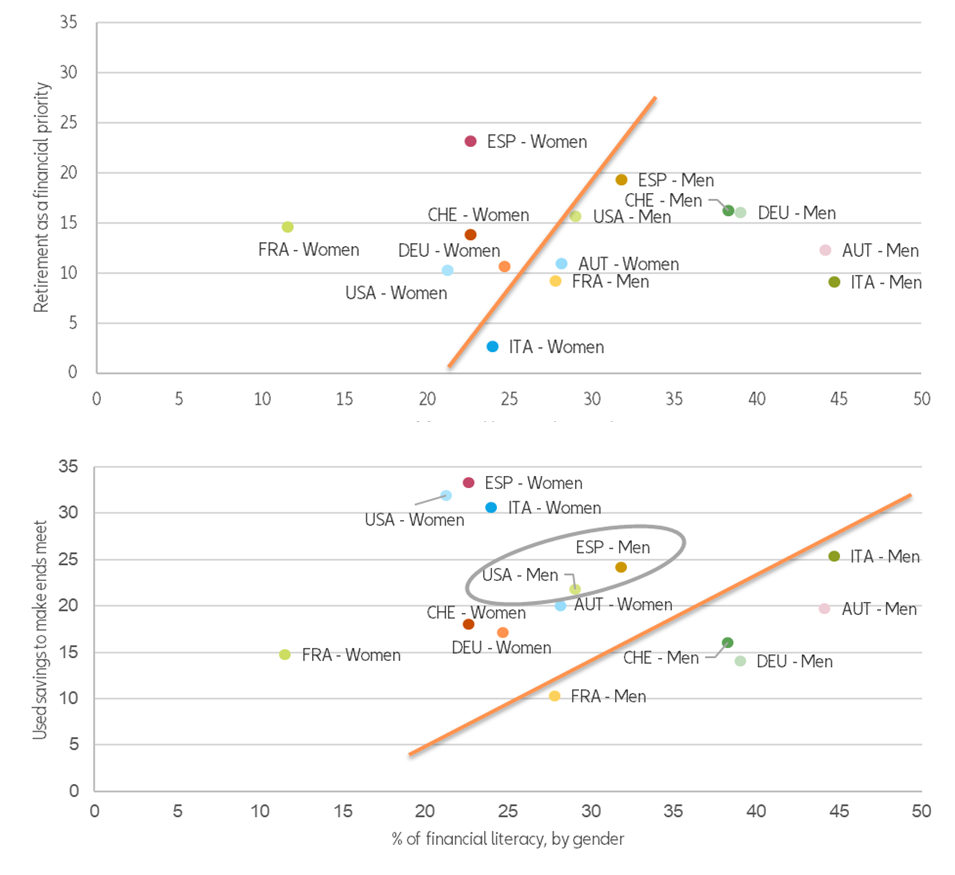

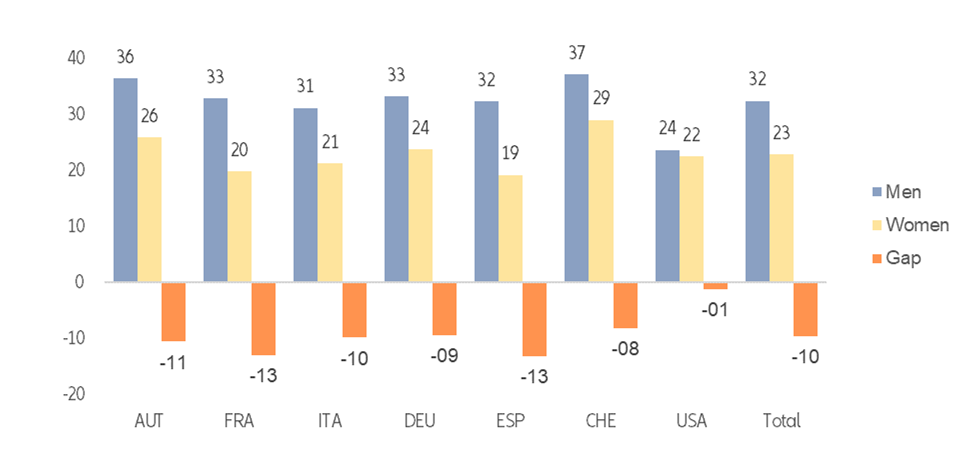

- Financial knowledge is a critical factor that explains why one segment of the population is better able to cope with the shock compared to others. However, our results show the level of financial literacy is disastrously low. To measure the level of financial literacy, we asked four questions relating to different financial skills: numeracy, interest, accounting, and inflation. Overall, only 28.5% of all respondents answered all four questions correctly. Even more alarmingly, we found a financial literacy gender gap in all countries: 36.4% of the men we surveyed were financially literate compared to 20.7% of the women in our sample. This added to the greater financial impact of women creates a perfect storm scenario for the pandemic to become a “she-cession”.

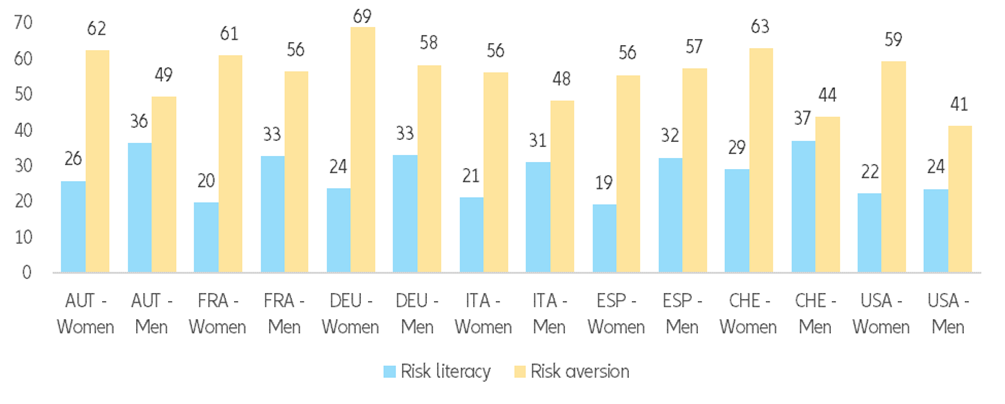

- The level of risk literacy is also (very) low (22.8%) and the gender gap pervasive (9.6 percentage points). But our survey could not prove the hypothesis that our risk profile is determined by our risk literacy: high-risk aversity could be found among “literate” as well as “illiterate” respondents. The on average higher risk aversity among female respondents’ points at other, unobservable factors like personality or social role expectations.

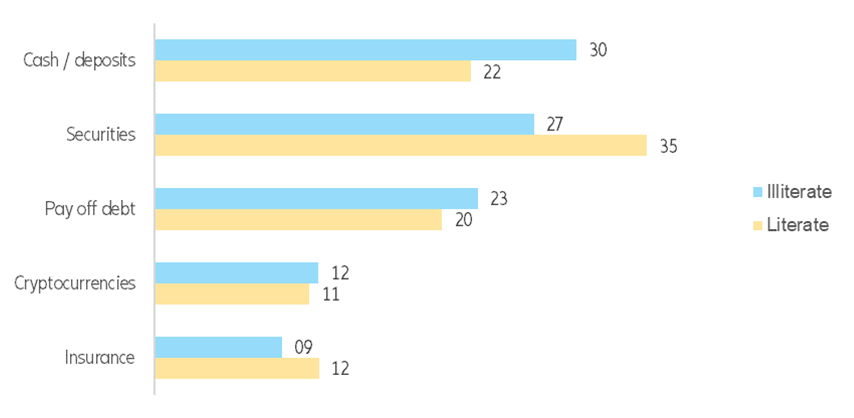

- Nevertheless, higher financial literacy seems to lead to better-informed investment decisions in times of negative real interest rates. When asked to invest EUR1,000, financially “literate” respondents preferred securities (35%) to bank deposits (22%); “illiterate” respondents answered the other way round (27% vs 30%). Thus, financially savvy savers are more likely to avoid falling into the trap of investing in supposedly safe but loss-making assets in times of negative real interest rates. Even more disturbing: “illiterate” respondents are more likely to invest in cryptocurrencies (12%) than in insurance related products (9%).

- What does this mean for policymakers and the finance industry? The disastrously low levels of financial and risk literacy are a call for action. The investment environment was challenging even before Covid-19 hit economies and markets. It has become more difficult ever since. Without sound knowledge, many households are doomed to make the wrong financial decisions, with devastating consequences for the financial well-being in the future. The upshot: Financial literacy should become part of the normal curriculum for schools and the industry should double down its efforts for simple, easy to understand products.

Introduction: Looking into households’ minds

Households have a great influence in the overall economy. If anything, the Covid-19 crisis is a brutal reminder of this obvious but often overlooked fact. Skyrocketing savings caused decreased demand and thus further affected the economic slump in the spring, while the return to shopping and travelling led to the equally forceful rebound over the summer. Going forward, the decisions of households – whether to save or spend – will be decisive, not just for their own financial well-being and the trajectory of economic growth, but also the monetary and financial stability of their countries as households’ resource allocation also affects market prices. Finally yet importantly, the ability of consumers to make informed financial decisions improves their ability to develop sound personal finance. Thus, as we navigate increasingly uncertain times, the decisions households take going forward will be crucial, not only to their financial well-being, but also to the economic stability of their countries.

Therefore, understanding the decision-making processes of households is of utmost importance. In recent years, research in this field – from behavioral finance to economic psychology – has made great strides. Based on these insights, we decided to conduct a survey to decipher the thoughts and motives that are driving spending and saving decisions at this critical juncture in time. In October 2020, we asked almost 7,000 people in seven countries to report the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on their economic decisions thus far, as well as some of their risk perceptions. These seven countries account for 40% of global GDP. We found striking results for how the pandemic has affected respondents in similar ways across Europe and the United States, as well as surprising heterogeneity in some responses by country, age and gender. Additionally, we asked a few questions related to inflation, interest rates (simple and compound) and probability in order to assess if households’ level of financial literacy itself had an effect on their self-reported changes in behavior. While we cannot credibly infer causality between financial literacy and the impact of Covid-19 for consumers – despite all theory-reinforcing statistical tests – we can acquire some insights into consumers’ minds in this period of uncertainty. Moreover, we will try to shed some light on their risk profiles and risk preferences using some of the questions in our survey.

Covid-19: A crisis unlike any other

The Covid-19 pandemic is the latest in a series of crises that has punctuated the first two decades of the 21st century. It is, however, different from the other crises, having started in the real economy rather than the financial sector, which was the origin of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009, the euro crisis and the one following the burst of the dotcom bubble. This time around, there have also been great efforts by governments to minimize the economic blow of lockdown(s), such as expansionary monetary policy, temporary debt relief, targeted interventions and expansion of existing programs, wage subsidies and temporary tax relief. Therefore, we wanted to know, eight months into the pandemic, whether consumers have felt an impact on their personal finances. Were there any other crises that weighed down their wallets more?

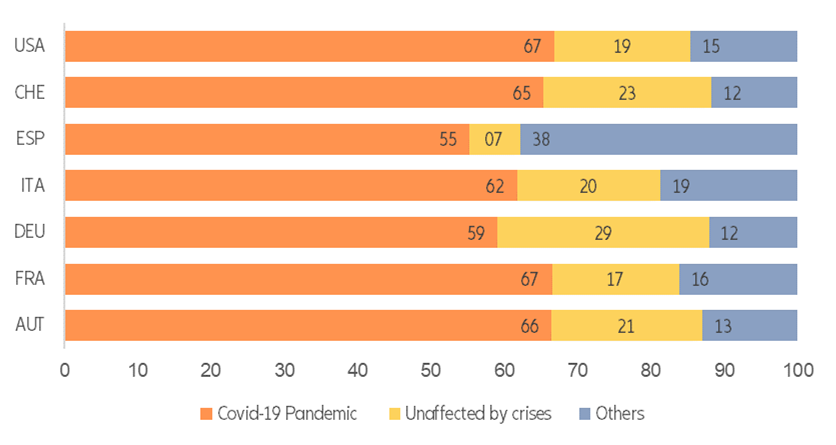

Across Europe, despite high levels of social protection in terms of social spending as a percentage of GDP, our results show that the Covid-19 crisis dwarfs all other crises in the magnitude of its impact on households, with 62.9% of respondents affected overall. The only exception is Spain: 22.9% of our total Spanish respondents considered the GFC, i.e. the implosion of the Spanish housing bubble, to have had a more long-lasting impact on their financial prosperity (against “only” 55.2% of respondents that say that Covid-19 has had the most damaging effect). Given that they went from the 2008 crisis straight into the euro crisis with no breaks in between, this outcome is hardly surprising. Six years of financial hardship are hard to forget. In contrast, 28.8% of all German respondents reported not having been affected by any of the crises in the last two decades, showing the highest level of resilience in our sample (see Figure 1). The other two countries with relative high crisis resilience are Switzerland, where 23% of total the respondents also said they had not suffered from any crises spanning from the dot-com bubble to the pandemic, and Austria, with 20.5% of respondents being unaffected.

In the U.S., the policy approach to preserve household stability is structurally different, resembling more of an ad-hoc cash transfer program than a welfare state measure. However, it has worked to a certain degree. 18.6% of our respondents from the ‘Land of the Free’ remained untouched by any of the crises in the past twenty years, less than in the DACH region, but considerably more than in Spain and even France.

Figure 1: A tale of a crisis-prone century

Question: Which economic crisis / shock would you consider would have the most long-term impact in your wellbeing and/or economic prosperity? Please choose one (in %).