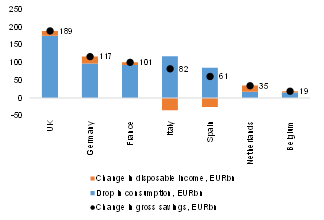

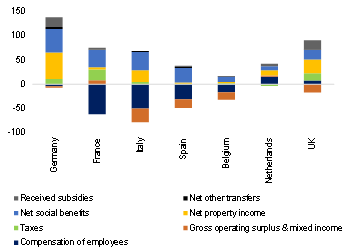

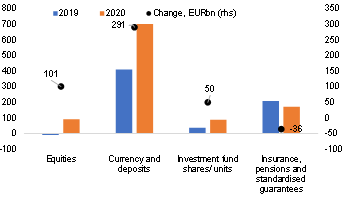

In 2021, the glut of excess savings could generate a double dividend for the Eurozone: first, a consumption boom of EUR170bn, or 1.5% of GDP. In 2020, gross savings in the Eurozone increased by more than +50%, and “excess savings” stood at more than EUR450bn, or over 4% of GDP, thanks to reduced spending on services amid renewed lockdowns . Extended support measures also played a role: along with partial unemployment schemes, lower taxation (including automatic stabilizers) and higher subsidies and net transfers supported gross disposable incomes , which remained more or less flat in the Eurozone in 2020 (see Figure 2). Overall, the excess savings in the Eurozone from 2020 represent almost one month of 2019 gross disposable income with more than one month in the UK and the Netherlands. Two thirds of households’ excess financial assets ended up in bank accounts while the remaining one third was invested in capital markets, mainly in equity. In 2020, Eurozone households turned from net sellers of equities into net buyers (see Figure 3), with the highest share of excess savings invested into equity seen in Germany (27%) and Italy (21%,) against 15% in France and 8% in Spain. In all countries, however, the share directly invested in equities is significantly above previous years’ levels, indicating a new interest in risky financial assets during the pandemic.

Figure 1 – Evolution of households’ gross savings in 2020, EURbn

Figure 2 – Main components which supported (+) or impaired (-) households’ disposable income in 2020, change in EURbn

Figure 3 – Eurozone household financial transactions, EURbn

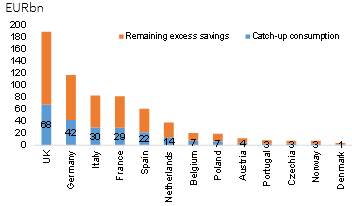

Taking into account the assumed structure of excess savings in 2020 (40% held by the 10% richest households, 50% by the upper-middle class and 10% for the remaining households), we look into the propensity to consume these excess savings over one year by income groups: 20% for the richest, 40% for the upper-middle class and 80% for the 1st to 5th income deciles. Hence, we find that at the Eurozone level, the potential catch-up in household consumption stands at around EUR170bn or 1.5% of GDP. This is eqivalent to more than one third of Covid-19 excess savings. Looking at individual countries, we estimate pent-up consumption in 2021 could reach EUR42bn in Germany, EUR68bn in the UK and EUR29bn in France (see Figure 4). This should be seen as a welcome boost to the recovery, with only a limited and temporary effect on prices (mainly in services).

Figure 4 – Pent-up consumption vs. remaining excess savings in 2021, EURbn

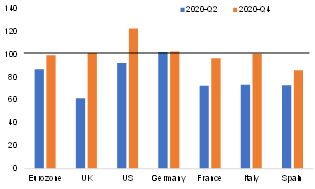

Nevertheless, roughly EUR300bn (2.9% of GDP) of excess savings will still remain at the Eurozone level, not to mention the EUR200bn of excess savings that might be added this year as a result of renewed lockdowns in H1 2021. Generally speaking, households have several options to use excess savings: either their financial assets remain untouched or they are transformed into consumption or into real assets (residential investments) or other financial assets (say, bank deposits into equities). As most households will see the remaining excess savings as a positive “wealth shock”, the most likely outcome might be the first option, i.e. these financial assets stay unchanged on households’ balance sheets. However, since a big chunk of excess savings is in the hands of the richest households, ”the housing option” also cannot be ruled out as these savers have a greater willingness and capability to invest in higher yielding assets, even if they are illiquid. In fact, the residential sector is already in a V-shape recovery (see Figure 5). Thus, a scenario in which these funds drive housing prices to even more frothy levels is a clear danger, with possible negative consequences down the road: cemented inequality as a large part of the population is simply barred from entering the housing market and heightened financial risks.

Figure 5 – Residential investment, 100 = pre-crisis level

Fortunately, there is a better way to make use of these excess savings to the benefit of savers, the financial markets and economies alike: as a source to accelerate the modernization and decarbonization of the European economy by speeding up the reform agenda for the Capital Market Union (CMU). This would be the second dividend. Excess savings in the EU, the amount of which is roughly equivalent to two-thirds of the Next Generation EU program, could give a tremendous boost to the green and digital transformation of the European economy. Channeling excess savings into this type of long-term investment would have several benefits: Households could earn decent returns; the growth potential of the EU economy would be lifted and, last but not least, the more harmful usages would be precluded: While a (moderate) boost to consumption is generally welcomed as a tailwind to the recovery, an unconstrained consumption or housing boom could prove rather destabilizing. A rush into the stock markets, too, could have rather detrimental effects at present, especially if many retail investors were to use the funds for speculative trades, comparable to the developments in the US.

This happy outcome, however, will by no means happen by itself. Without the right incentives, the bulk of excess savings might remain sitting idle in bank accounts or find their way into less beneficial investments. Thus, policymakers are called upon to set the right course so that excess savings can unleash their potentially beneficial effects. To amplify the impact, it would also make sense to use the mobilization of excess savings as the initial spark for the CMU from the retail side. The EU Commission is currently implementing an action plan to strengthen and complete the CMU. In the context of excess savings, one measure in particular is of importance: the revision of the legislative framework for ELTIFs (European long-term investment funds). ELTIFs have been around for years, but so far they have had a rather shadowy existence and hardly address retail investors. This should change. The idea behind ELTIFs is compelling: they are a vehicle for investing safely in illiquid assets, from start-ups to infrastructure projects. As is so often the case in the EU, however, implementation has fallen (far) short of plans: too restrictive and complicated.

Four measures are needed to make ELTIFs into attractive financial products for retail investors: more flexible investment guidelines, more flexible redemption rules, lower sales hurdles and, above all, favorable tax regimes. So far, ELTIFs have been treated very differently in EU countries in terms of taxation – and in some cases even disadvantaged compared with similar investments. This is where countermeasures need to be taken. Not only tax advantages are conceivable, but also direct subsidies: Governments could top up each investment with EUR20 for every EUR100 invested, up to certain limit. It would be an initiative that is easily understood and should prove popular. The funds for this could come directly from the Next Generation EU program, an elegant way to leverage its effectiveness.

At the same time, the tax patchwork in ELTIFs points to a general problem of the CMU from an investor's perspective: The current EU-wide disparate withholding tax levels and refunding processes pose barriers to the free movement of capital and significant obstacles to investment, thus impeding the completion of the CMU. There is an urgent need for action and harmonization here. The challenge of channeling private excess savings into long-term investments for the green and digital transformation is central to the promise of "building back better." With the CMU and ELTIFs, the EU already has appropriate vehicles. They just need to be made fit for the purpose. Otherwise, excess savings could become just another element to fray the social fabric.