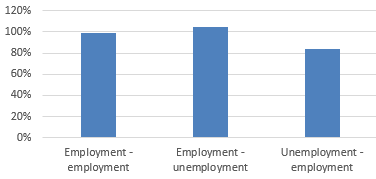

Employment-retention schemes propped up more than 25 million workers in the big four Eurozone economies alone in the immediate aftermath of the Covid-19 shock. In fact, thanks to these schemes, labor market flows from employment to unemployment in 2020 barely exceeded those in 2019, despite the sharp growth setback. On the flipside, however, 13.7 million unemployed workers have to a large degree been frozen out of employment as severely depressed transitions from unemployment to employment (-20%) in 2020 underline (Figure 1). Given the at best gradual defrosting of Eurozone labor markets over the coming year, coupled with the prospects of a jobless recovery, we see a heightened risk that the cyclical labor market shock turns structural, with unemployment stabilizing at an elevated level.

Figure 1 – 2020 labor market flows as a share of 2019 flows (%)

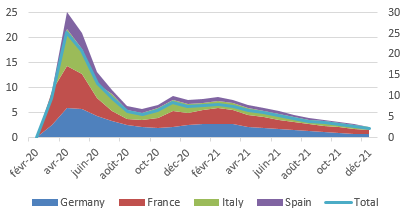

First out, last in: No rapid return trip into employment for the jobless. The vast majority of workers that lost their jobs in H1 2020, or were already unemployed before that, will struggle to return into employment over the coming 12 months. After all, as the Eurozone economic recovery starts to unfold from the second quarter of 2021 onwards, firms will prioritize reabsorbing furloughed workers (by increasing their working hours) over hiring new ones. Even though the number of furloughed workers across the four large Eurozone economies has fallen from a peak of 25 million in April 2020 to just below 8 million in December (Figure 2), this process will prove gradual at best for several reasons: 1) reabsorbing furloughed workers is easier said than done. After all, firms will see notable cost increases, given the need to pay wages as well as social security contributions, which will add pressure on already battered corporate margins, particularly in the early recovery phase. 2) Germany will reach pre-crisis GDP levels only by mid-2022, while Italy, Spain and France will require one additional year to heal. Given elections in Germany in September 2021, in France in April 2022 and in Italy in 2023, expect governments to generously extend the duration of schemes into 2022, though this support could become more targeted. As a result, we expect to enter 2022 with 2 million workers still benefitting from furlough schemes.

Figure 2 – Furloughed workers in the four big Eurozone economies (in million)

With broad-based hiring unlikely to take-off before 2022, re-employment prospects for those searching a job (13.7 million as of December 2020, 1.8 million of which have been added since February – leaving out the “

hidden unemployed” i.e. workers that have dropped out of the labor force) remain dim.

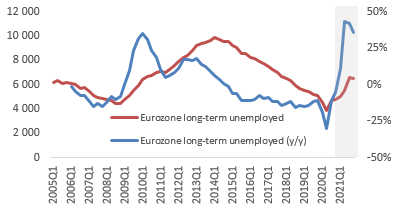

As a result, we expect long-term unemployment to rise +38% above pre-Covid-19 levels in 2021 — from an estimated pre-crisis low of 4.8 million people in Q1 2020 to 6.6 million in Q3 2021 before slightly leveling off in Q4 2021 to 6.5 million. Note that over 2020, long term employment was very volatile due to the lockdown, bottoming at 2.8 million in Q2 2020 because of dropouts.

Figure 3 – Eurozone: Long-term unemployment (thousands & y/y in %)

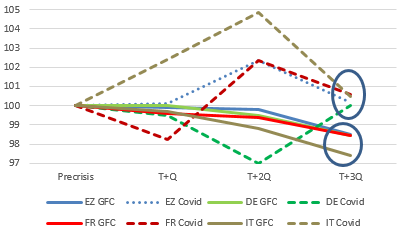

Mind the risk of a jobless recovery: Structural headwinds may further complicate reemployment prospects even after labor markets are defrosted. Long-term joblessness can serve as a proxy for structural unemployment. After all, prospects of reemployment steadily reduce with the duration of unemployment due to, among other factors, the negative impact on a person’s skills. The Covid-19-shock has accelerated structural changes in the economy, which in turn are likely to fuel the mismatch between workers and job profiles. In particular, there is some evidence that labor productivity may have been boosted by the Covid-19 shock. In fact, productivity per hour worked rose above pre-crisis levels as soon as Q3 2020. In fact, this is in sharp contrast to the productivity per hour worked trend observed during the great financial crisis (Figure 4). While it is still early days, one interpretation could be that the pandemic forced digitalization on Europe, with widespread remote working and an increased degree of automation in production being potential drivers of a productivity boost.

Figure 4 – Real productivity per hour worked, index: 100 = pre-crisis level

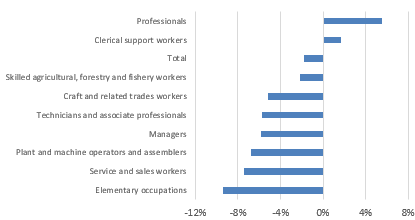

With job losses in 2020 largely centered on routine occupations (Figure 5), we see the risk of Europe following in the footsteps of the US, where “jobless recoveries” and rising “job market polarization” have arguably already become the new norm in the context of a higher rate of technological adoption. What initially looked like cyclical job-shedding in the Eurozone may turn out to become a structural problem, with negative repercussions on reemployment prospects for jobless workers,

as well as resulting in the rise of “zombie jobs”.

Figure 5 – Eurozone: Employment in Q3 2020 vs. Q3 2019 (in %)

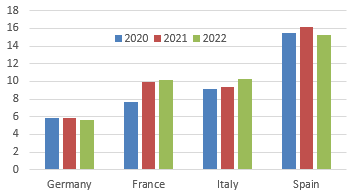

Our forecasts for joblessness in the large Eurozone economies (Figure 6) reflects persistent labor market headwinds with unemployment rates in France and Italy peaking only in 2022 while remaining at an elevated level in Germany and Spain.

Figure 6 – Unemployment rate (%)

Policymakers are in for a mammoth job: Elevated structural unemployment would not only have a negative impact on the productive capacity of the economy but also carries the potential to exacerbate already prevailing political discontent and fuel social unrest. So far Eurozone countries are devoting insufficient resources to improve the odds of workers becoming re-employed once the recovery sets in. Meanwhile, the Covid-19-shock has in fact reduced measures on offer. For instance, in Germany in January 2021, the number of workers participating in active labor market policy initiatives was down more than 4% compared to one year ago. To mitigate the scarring impact on Eurozone labor markets and keep a lid on structural unemployment, workers need to be equipped with the skills required to fill the jobs of tomorrow. In the presence of a skills mismatch, hiring incentives won’t do the trick here. Rather, active labor market policies, with a focus on rapid upskilling and reskilling, will be key to boosting workers’ employability and to keep a lid on the growing wedge in labor markets between high- and low-skilled workers. Moreover, for a comprehensive approach, more structural remedies, including an overhaul of education systems, will also need to be considered.