Executive Summary

- The Asia-Pacific region has fared better than most other regions during the Covid-19 crisis: Economic activity is likely to have declined by less than -2% in 2020, compared to more than -4% at the global level and almost -8% in Latin America. But labor markets were hit hard, predominantly impacting poor and low-income earners, who work often in the informal labor market with limited access to social security. This has spurred income inequality in many markets.

- The pandemic poses only a brief interruption to the aging trend in Asia: Within the next thirty years, Asia’s population of those aged 65 years and older is expected to more than double from around 412mn today to 955mn in 2050; the share of this age group in the total population is set to reach 18% by then.

- There are still marked differences in the development stages of the region’s pension systems, not least when comparing pension coverage ratios, which span from 3% in Cambodia to 100% in Japan. Equally huge disparities can be observed in private wealth in Taiwan, where net financial assets by households accounted for more than 400% of total GDP in 2019, while in Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines the corresponding figure was less than 50%.

- The main cause of concern with respect to the long-term sustainability is the pension age in many markets, which does not reflect the gains in life expectancy over the last decades. And although some markets are discussing an increase in the retirement age, the planned changes might not be sufficient to level the expected increases in further life expectancy.

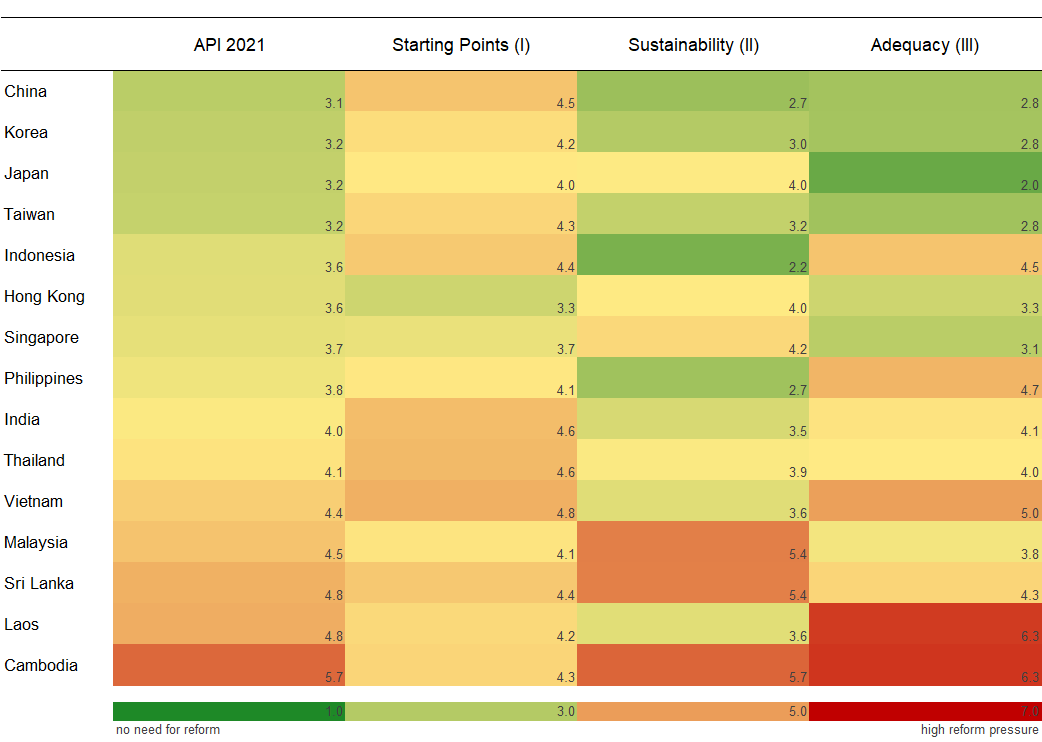

- The message of our proprietary Allianz Pension Indicator (API) is clear: There is no market in Asia that doesn’t need pension reforms. The necessary breadth and depth of reforms might differ – but not their urgency. The looming demographic crisis does not allow for pension and financial system reforms to be put on the back burner.

A temporary hit with lasting effects on inequality – but not on aging

At the time of writing, the Covid-19 pandemic has already caused more than 2mn premature deaths worldwide, along with the most severe economic downturn since the Second World War. In 2020, global GDP is likely to have slumped by more than -4%, surpassing the contraction seen during 2009 Great Financial Crisis by a wide margin (-0.1% in 2009). Although governments took unprecedented fiscal measures to mitigate the blow to livelihoods, Covid-19 has exacerbated existing inequalities which will probably still felt be in years from now. Scars will remain not only from the deep recession, rising unemployment and interrupted education but also from some of the support measures, which may backfire in the long run. Short-term fixes such as the temporary reduction or suspension of pension contributions or the temporary allowance to withdraw pension fund savings to ease financial burdens could increase the likelihood of old-age poverty in the years to come.

Like fiscal policies, monetary policies, too, came to the rescue and flooded markets with ample liquidity. Here, too, the results are ambiguous. On the one hand, the latest available figures indicate that private households’ financial assets proved to be almost immune to the virus. In most markets, the Covid-19 crisis is expected to leave nothing but a dip in the assets growth rate as capital markets have rallied since the March 2020 turbulence and savings rates leaped following lockdowns and reduced consumption opportunities. On the other hand, there are also some developments that raise concerns: ultra-low interest-fueled credit-financed consumption and rising public expenditure, leading to a sharp increase in loan-to-GDP ratios. As lower income groups were especially hit by the crisis, they were also the ones who had to take out credit or make use of the offer to withdraw pension fund assets, tapping into their often already meagre savings for old age. As a consequence, the income and wealth gap has become wider.

Thus, one of the (unwelcome) legacies of the crisis and temporary stimulus measures such as the reductions in pension savings might be a higher number of the elderly who depend on social welfare in old age in the long run. Given the still very young populations in most Asian markets, old-age poverty currently seems to be only a minor problem. But the rapid aging of Asian societies, only briefly halted by Covid-19, will turn it into a major one if there are no efforts to build demography-proof pension systems, which would also be an important stabilizer in economic downturns, thanks to the consumption expenditures of pensioners.

In order to cushion the impact of population aging on pay-as-you-go financed pension systems, complementary capital-funded old-age provision is going to be necessary to secure a decent living standard in old age. Thus, increasing the access to financial services and further efforts to improve financial literacy are indispensable.

This report aims at giving an overview on the current state of the pension systems in the region and future reform needs in order to make them demography-proof, guided by our proprietary Allianz Pension Indicator. It also includes an analysis of private households’ financial asset structure that hints at the awareness of the need for private pension provision, the accessibility of financial services and thus, last but not least, the development stage of the financial system.

Asia has weathered the Covid-19 crisis in relatively good shape, and its starting position for the 2020s is better than in most other regions. However, it should not forfeit its advantage by ignoring the looming demographic crisis. The next generations of Asians would have to pay a heavy price for such negligence, and it could even spell the premature end of the Asian century. It’s time to act.

The Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on growth, inequality and aging

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused the most severe economic contraction in decades. The Asia-Pacific region, however, has fared better than most. For 2020, our projections point to a decline in economic activity of less than -2% in the region while global output is likely to have shrunk by more than -4%; in Latin America, for example, GDP would have slumped by almost -8%.

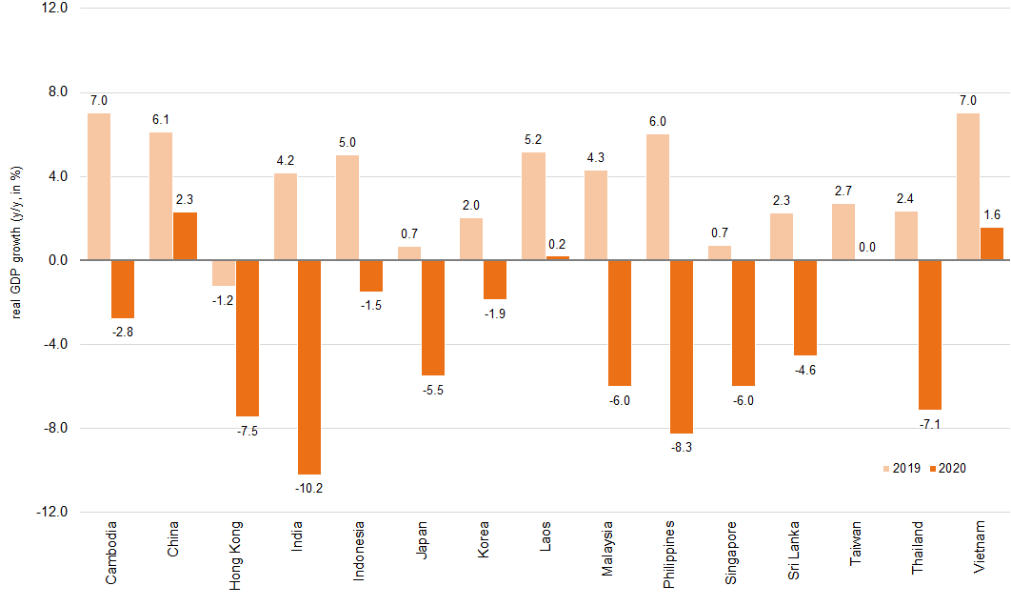

Asia-Pacific’s modest fall in economic activity, however, conceals an unusually large dispersion of performance within the region: The hardest hit countries in the region include India, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Thailand. The Indian economy, for example, is expected to have shrunk by -10.2% in 2020. China, on the other hand, has already reported real growth of +2.3% in 2020. The other heavyweight of the region, Japan, was in between, with a GDP decline of -5.5% in 2020. All in all, these numbers are a far cry from the dynamic development that was observed just one year before: In 2019, real growth rates in the region’s emerging economies ranged between +4.2% and +7.0% (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Covodi-19 pandemic took a toll on economic growth

Sources: IMF, Allianz Research.

Although the pandemic crisis was not as severe in Asia as in other parts of the world, it wreaked havoc on the labor markets. Rising unemployment rates and reductions of working hours equaled 30 million full time jobs lost in the third quarter of 2020 alone . Those hit were the poor and low-income earners who often work in the informal labor market with limited access to social security, thus spurring income inequality in many markets. These inequalities will also translate into inequalities in old age as many low-income earners do neither have access to a public or occupational pension system nor enough earnings for private old-age provision. Temporary reductions of contribution rates to or granting the possibility to draw from employee provident funds, as seen in China, Malaysia and Singapore, could also increase the gap. As lower income households are particularly set to make use of these offers, they will face reduced pension income in the future. Thus, the Covid-19 pandemic has shown the importance of functioning social security systems. This also holds true for public pension provision, not only from an individual point of view, but also from the macroeconomic perspective: an adequate pension system that provides a decent living standard in old age tends to have a stabilizing effect on consumption in times of crisis.

By causing millions of premature deaths around the world, the Covid-19 crisis also reduced the average period life expectancy in 2020 by several months, in some markets maybe even years. But the underlying demographic trends are going to remain intact: Due to decreasing fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, the world’s population will continue to age.

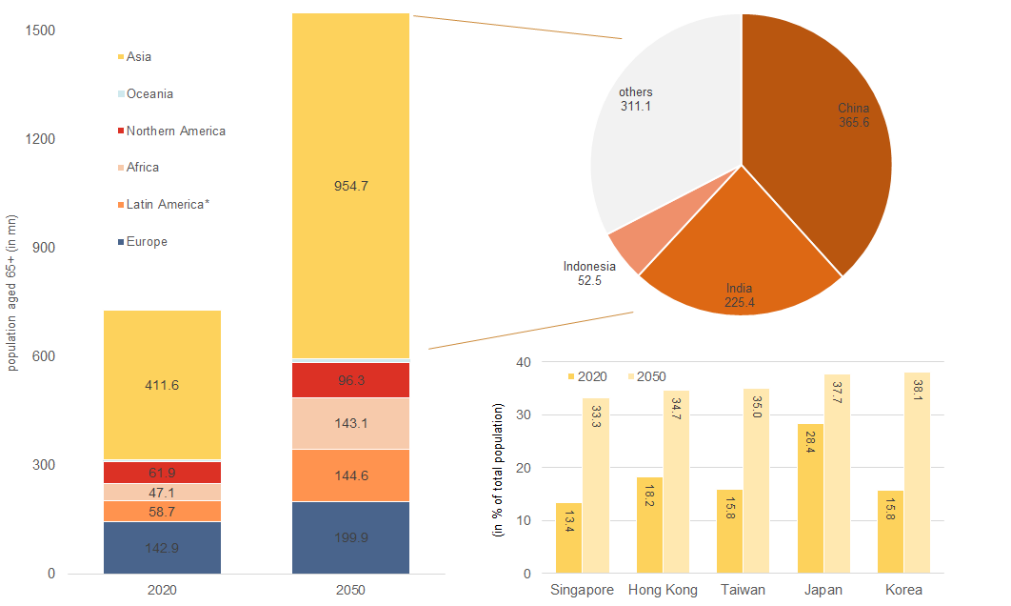

Asia is one of the regions where the outcomes of this trend are going to be most evident. Within the next thirty years, Asia’s population aged 65 years and older is expected to more than double from around 412mn today to 955mn in 2050; the share of this age group in the total population is set to reach 18% by then. That means, in some Asian markets, the share of the elderly is set to more than double within less than a generation; in Europe, this took more than 50 years.

In 2050, around two thirds of Asia’s population aged 65 and older will be located in just three markets: 366mn, i.e. more than a third, in China, 225mn in India and 52mn in Indonesia, which will have surpassed Japan as the place with the third-highest number of elderly citizens in Asia by then. South Korea is set to replace Japan as the place with the oldest population in Asia; together with Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and Taiwan, it will be among the ten markets with the oldest populations worldwide. By mid-century, in all five markets, at least one third of the population will be aged 65 or older, with the shares in Japan and South Korea reaching almost 40%. This is all the more remarkable as Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong still have relatively young populations today, with the share of the elderly ranging between 13.4% and 18.2% (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: In 2050, 955mn of the world’s 1.5bn elderly people will live in Asia

Source: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019).

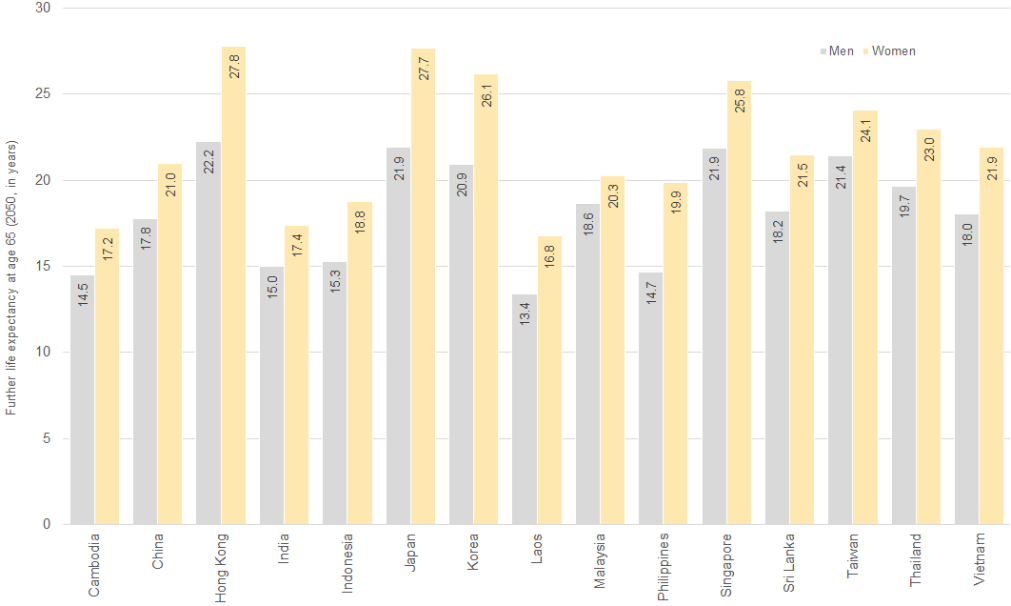

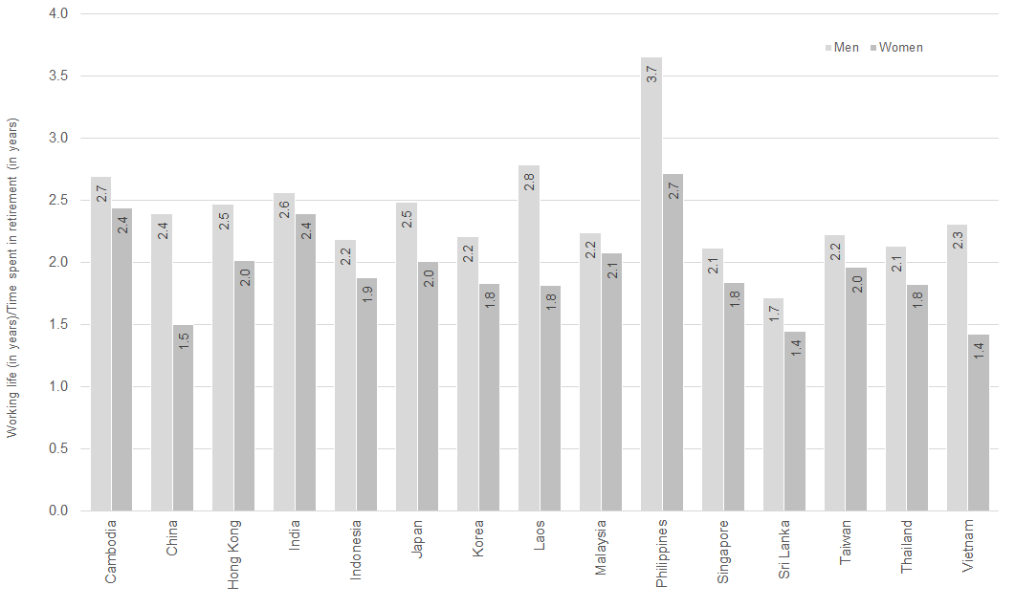

By 2050, the average life expectancy of 65 year olds is also set to increase further. Among the markets covered in our report, Laos and Hong Kong set the borders: The average further life expectancy is set to range from 13.4 years in Laos to 22.2 years in Hong Kong for males, and between 16.8 years and 27.8 years for women (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: In most Asian markets, women are set to spend more than 20 years in retirement

Source: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019).

Thus, one of the main future challenges will be how to finance the longer retirement periods of an increasing number of people. Combined with the breakup of traditional family structures, not least due to decreasing fertility rates , there is a rising need for sustainable pension systems that guarantee a decent living standard in old age. Though the development stages of Asia’s pension systems differ markedly, they have one thing in common: The window of opportunity to make them demography-proof is gradually getting smaller.

Besides the rapid demographic change, most markets have one further argument in common for striving for demography-proof i.e. sustainable and adequate pension systems: Due to their fiscal support measures to cushion the impact of the Covid-19 crisis, general government gross debt has increased and thus their future financial leeway to subsidize pension systems has shrunk. However, there are marked differences with respect to the degree of indebtedness: while the gross budget deficit of Japan is expected to reach 266%, that of Hong Kong will probably remain below 1% (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Covid-19 crisis has diminished governments’ financial leeway

Source: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019).

Different starting points for pension reforms in Asia

There are marked differences between the 15 Asian markets that we cover in our report with respect to the overall development stage and prosperity level, as well as the pension system.

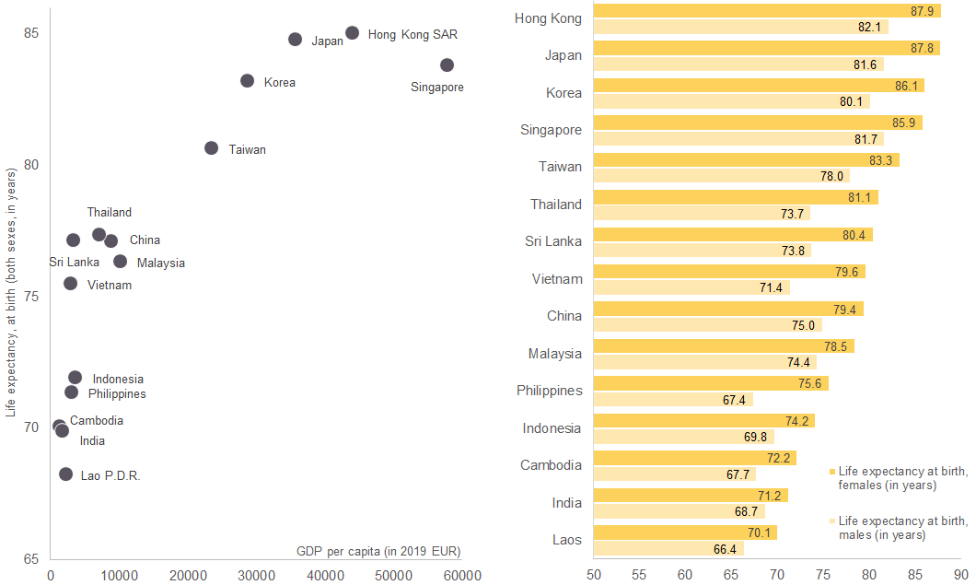

The GDP per capita and average life expectancy at birth are indicators for the overall development stage of a market. Both factors are positively correlated: The higher the GDP per capita, the higher in general the average life expectancy. Among the 15 markets we cover in this report are on the one hand three with the highest average life expectancy worldwide, namely Hong Kong, Japan and Singapore, and one with the lowest in Asia, Laos. According to the latest available UN estimates, the difference in average life expectancy at birth was 17.2 years, ranging from 68.2 years in Laos, where GDP per capita amounted to merely EUR2,290 at the end of 2019, to 85.0 years in Hong Kong, where GDP per capita was EUR44,060 or almost 20 times that of Laos (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: GDP per capita and average life expectancy as indicators for prosperity

Source: UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019).

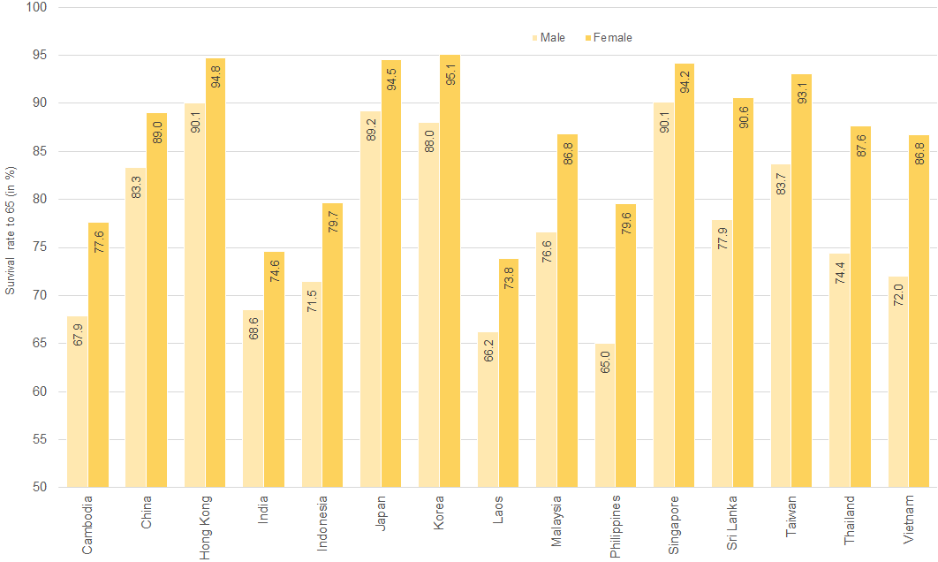

Babies born in the richer Asian markets can also expect to spend a longer time of their lives in good health than those born in the poorer markets due to higher living standards, including better access to medical services. The healthy life expectancy at birth ranged between an average 60 years in India to more than 74 years in Japan. As a consequence, they also have a markedly higher chance to reach the age of 65 than their peers in poorer markets. While only 65% of newborn boys in the Philippines could expect to celebrate their 65th birthday, this held true for more than 90% of those born in Singapore. The respective shares for newborn girls ranged from 74% to almost 95% in Hong Kong (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Chance of reaching the age of 65

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators.

Furthermore, the degree of urbanization, the share of employment in agriculture and the share of internet users in the population have an impact on the access to pension coverage and financial services. The more people are employed in the formal sector, i.e., the industrial and service sector, the higher is the coverage of (formal) public and occupational pension systems. In markets with a higher degree of urbanization, it is often easier to provide access to financial services than in states where a large part of the population lives in remote areas. And the use of the internet is an indicator for the access to information and online (financial) services. The 15 markets differ markedly in these respects: While Singapore is a city-state with 100% of its population living in urban areas and a mere 0.7% of the labor force still working in agriculture, more than 80% of Sri Lanka’s population live in rural areas and almost 62% are employed in agriculture in Laos. The same holds true for internet use: with more than 96%, South Korea has the highest share of internet users of the markets, in contrast to Laos, where only 25% use the internet.

Thus, the preconditions and prosperity levels differ markedly between the analyzed markets. While Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan are among the markets with the highest living standards in the world, boasting well-developed – though not necessarily long-term sustainable – pension systems, there is still marked backlog demand for old-age protection in Cambodia, Laos and India, where living standards are generally lower. Thus, the differences with respect to the urgency of and the reason for pension reforms between the markets in Asia are huge.

Though there is broad consensus about the need of a sustainable and adequate pension system and ongoing discussions in many markets about necessary increases of the retirement age with respect to rising life expectancy, there are still marked differences in the development stages of the region’s pension systems. These become most obvious when comparing the coverage ratios and the public spending for old age, with low levels of the latter in some markets not only reflecting the favorable age structure of the population but rather the low development stage of the pension system.

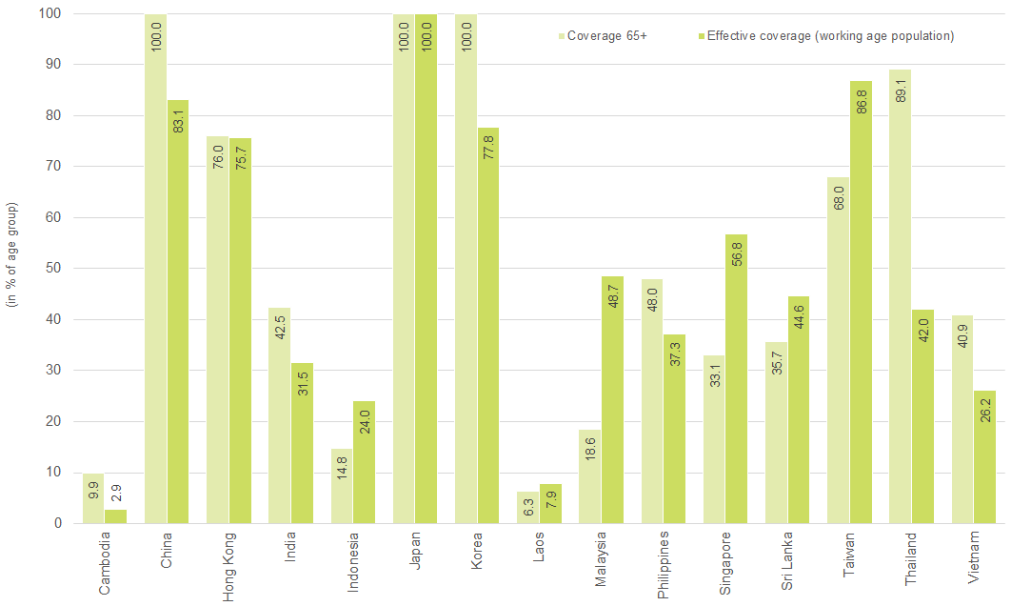

According to latest available ILO data, the pension coverage of the working age population ranges between a mere 3% in Cambodia to100% in Japan. And while in China, Japan and South Korea every inhabitant aged 65 and older is covered, only 7% of Lao’s elderly population receives a pension (see Figure 7). In some countries, like Laos, India and Cambodia, it is mainly public sector employees who are covered by pension systems, while workers who are often employed in the informal sector have no access to the public pension system . However, universal pension coverage does not automatically imply an equal distribution of pension income: a recently published survey found marked inequalities between rural and urban pensions in China , for example.

Figure 7: Marked differences in pension coverage

Unfortunately, the markets with low pension coverage rates are in most cases also those where the financial system and thus the means for private pension provision are still rather underdeveloped. The indicators for this are the share of the population with an account at a financial institution, private households’ asset structure and the sum of private households’ net financial assets compared to GDP.

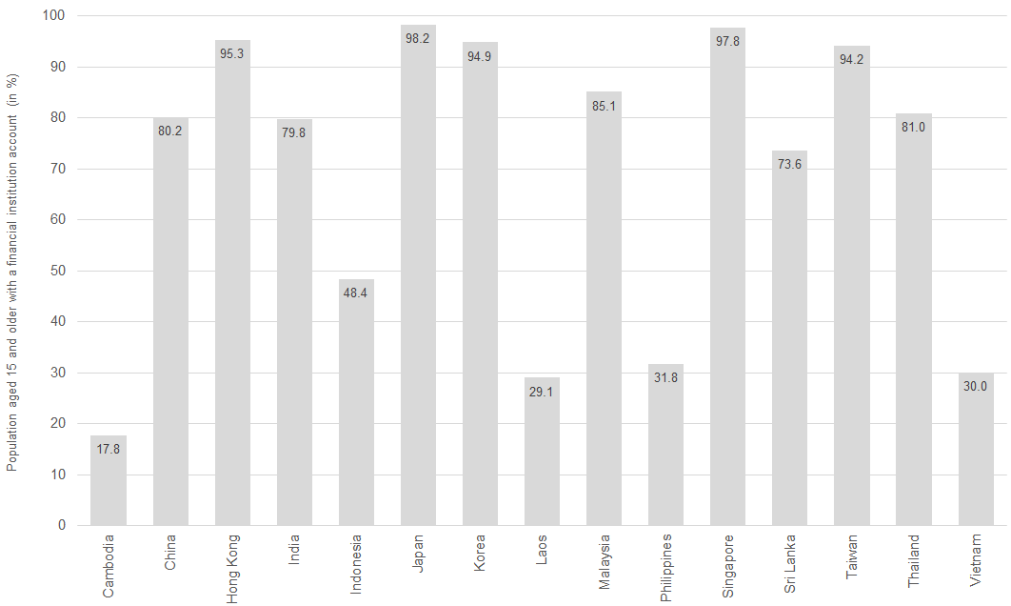

In Cambodia, Laos, the Philippines and Vietnam, less than a third of the population aged 15 and older had an account at a financial institution, while in the rich city states Hong Kong and Singapore, as well as in Japan, Taiwan and South Korea, close to 100% of the population had their own account. In the remaining markets there is still backlog demand, but due to government efforts the accessibility of financial services has already improved markedly in recent years (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Access to financial services – crucial for private old age provision

Sources: World Bank, Global Findex Database.

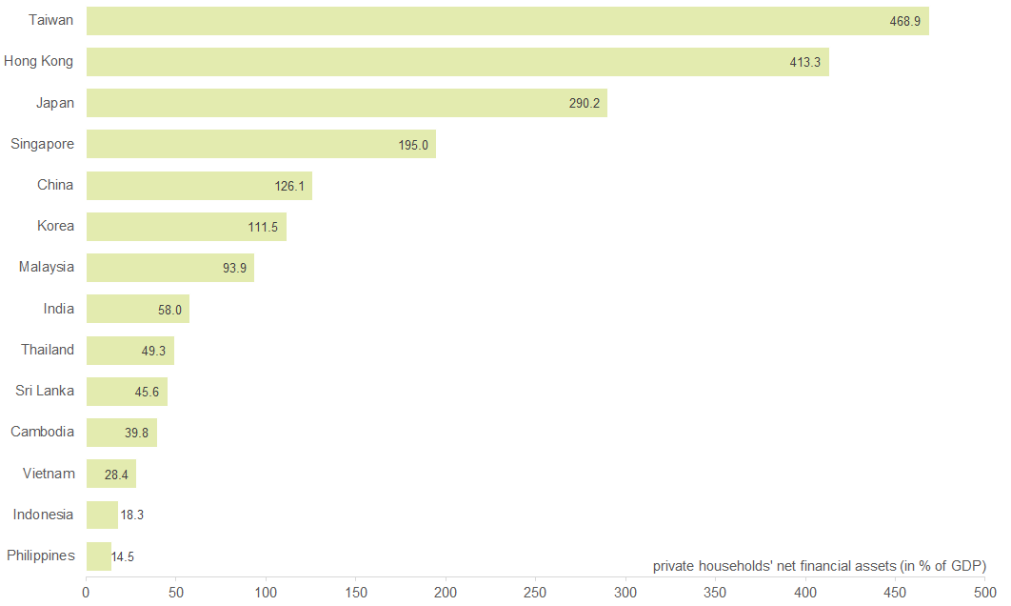

The access to financial services corresponds with the size of private households’ financial assets and the portfolio structure. Of course, the richest markets in the region, measured in GDP per capita, are also the markets with the highest financial assets. In Taiwan, net financial assets accounted for more than 450% of total GDP, while in Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines they amounted to less than 50% of the respective GDP (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Marked differences in private households’ net financial assets (2019)

Source: Allianz Global Wealth Report 2020.

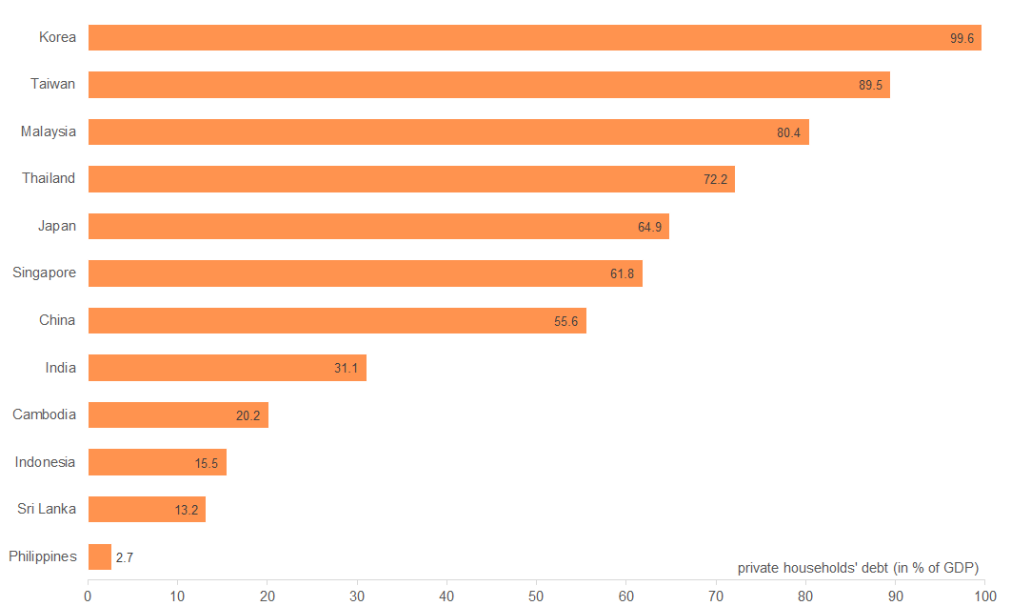

In some markets, the indebtedness of private households is a cause for concern. At the end of 2019, the debt-to-GDP ratios in Thailand, South Korea and Malaysia were already above 80% (see Figure 10). The latest available data indicate that in the course of the crisis, the debt-to-GDP has increased further in some markets. In Malaysia, for example, it increased to 87.5% at the end of the third quarter of 2020, especially due to a rise in car loans that was triggered by a government stimulus programs cutting the sales taxes on cars . In contrast, we observe a consolidation in Singapore, for example, where credit card loans in particular decreased markedly. However as the GDP downturn has probably outpaced the decline in loans, even here the indebtedness ratio is expected to increase despite households’ discipline .

Figure 10: Marked differences in households’ indebtedness (2019)

Source: Allianz Global Wealth Report 2020.

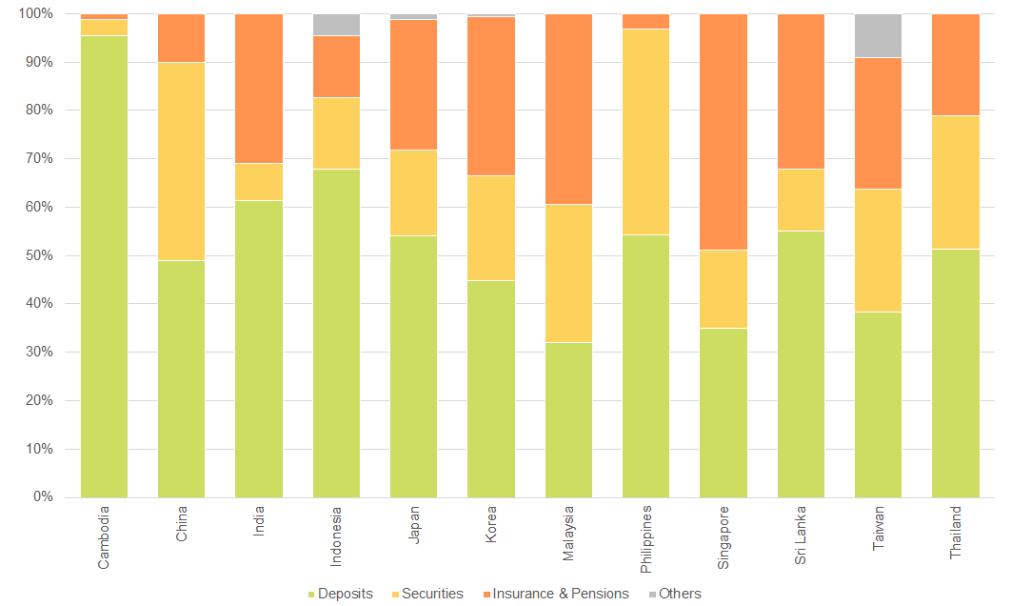

Furthermore, we also observe differences in the asset structure of private households, which reflects not only the overall development stage of the financial system and the accessibility of financial services but also the awareness of the need for old-age provision. In markets with less-developed financial systems such as Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, bank deposits are still the dominating asset class, with shares in total assets markedly above 50%. In the other markets, life insurance and pension products as well as securities play a more important role. The only exception is Japan, where the subdued development of the stock market – the Nikkei only picked up in recent years and reached a value close that seen in 1991 for the first time at the end of 2017 – and some distortions on the life insurance market, bank deposits are the first choice asset class (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Asset structure of households (2019)

Source: Allianz Global Wealth Report 2020.

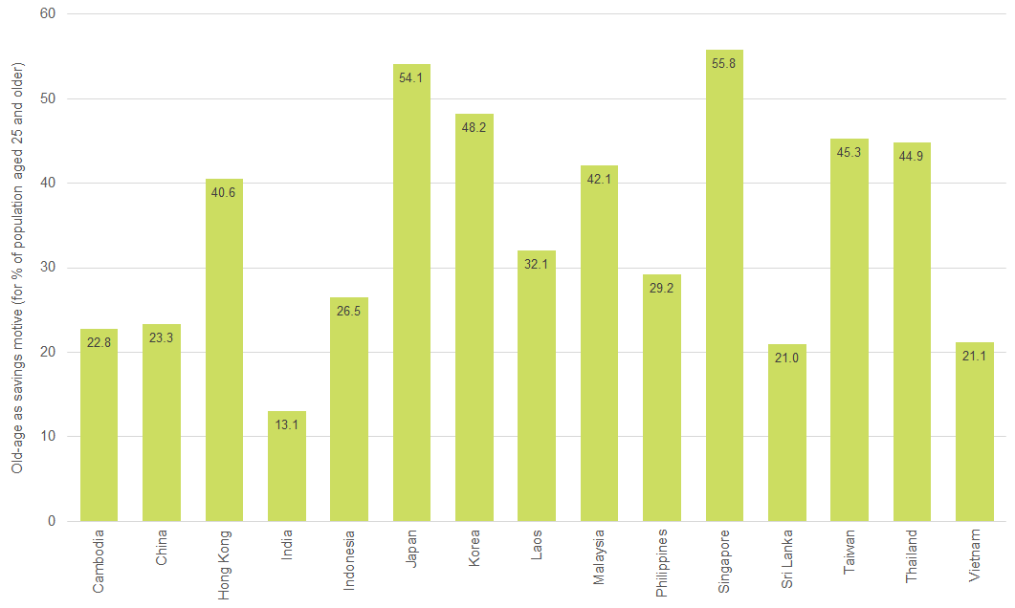

The continued lack of awareness of the need to make a private pension provision becomes evident in the responses to the question about the savings motive in the World Bank’s Global Findex Database. The awareness of the need to save for old age was highest in the rapidly aging markets, such as Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Hong Kong. In contrast, in those markets with younger populations – and less developed financial systems – old age played only a minor role as a savings motive (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: Old-age saving plays a minor role in emerging markets

Source: World Bank, Global Findex Database.

The elephant in the room of pension reform: Retirement age

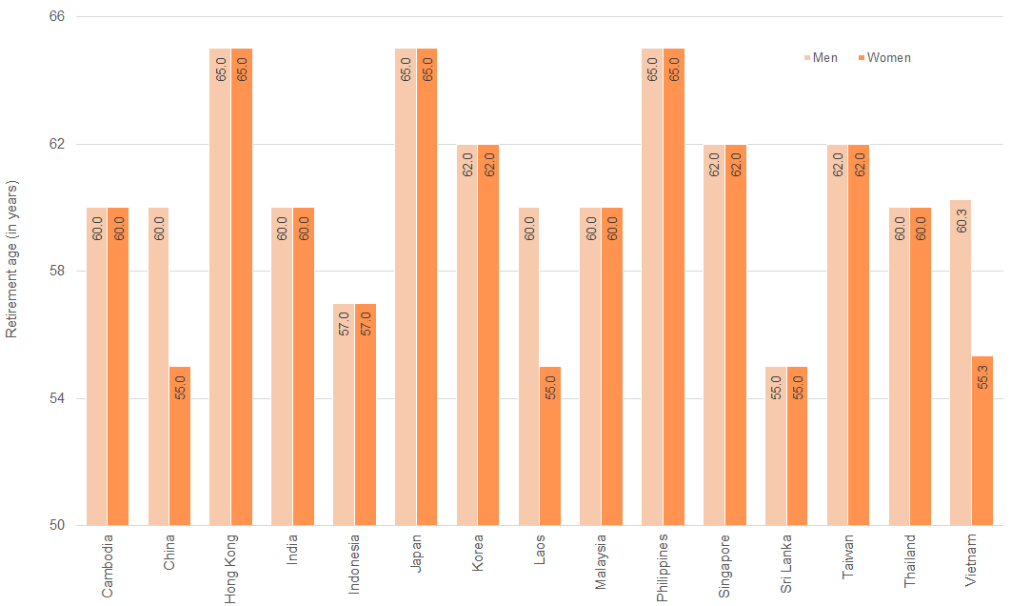

The main cause of concern with respect to long-term sustainability is the pension age in many markets, which does not reflect the gains in life expectancy over the last decades. We observe ongoing discussions in many markets in the region, but only a few have already decided to implement pension reforms in this respect. However, it is rather questionable whether the planned increases in retirement age are sufficient to offset the expected increases in further life expectancy, which is unlikely to change despite the Covid-19 pandemic.

The agreed upon or statutory retirement ages range between 55 and 65 years (see Figure 13). However, in some markets, such as Singapore and Thailand, the retirement age only marks the age limit until which an employer is not allowed to cancel a contract because of age reasons. In both markets, many employees choose to work until the age of 65 or longer if possible. In Singapore, the so-called re-employment age is currently 67 and set to be increased to 70 until 2028.

Figure 13: Retirement ages differ markedly

Sources: National ministries of finance, national ministries of social affairs, national pension providers, OECD, ISSA.

But in most markets the time period that will be spent in retirement is relatively long compared to the working life, even if we assume that the latter starts at age 15. This holds especially true for Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan, which are among the markets with the highest further life expectancies in the world (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: Low work-life-to-retirement balances* in wealthy Asian markets

Sources: National ministries of finance, national ministries of social affairs, national pension providers, OECD, ISSA, UN, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2019).

This mismatch not only poses a problem for pay-as-you-go financed pension systems, where a shrinking number of people of working age has to finance the pensions of an increasing number of people in retirement age, but also for merely capital-funded systems. If the pension age is not adjusted accordingly, the contributions must increase markedly to make sure that savers build enough capital to guarantee a decent living standard in old age, otherwise they have to face lower benefit levels. And if a tax-financed welfare program is in place, that grants means-tested subsidies for pensioners with pension income below a certain threshold, like the Silver Support scheme in Singapore, neglected adjustments might inevitably lead to higher welfare expenditures in the long run.

In this context, pension and financial system reforms should not be put on the back burner for too long in order to make sure that there is still enough time to build up demography-proof pension systems and adequate old-age savings. In this respect, nearly all markets in the region still need reforms (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Allianz Pension Indicator (API) points at need for pension reforms

Source: Allianz Research.